Australia in the Vietnam War

A Case Studies in Foreign Policy Analysis

1945 The Saigon Insurrection

www.hotkey.net.au/~marshalle/history/1945.htm

PrintCloseOne of the main concerns of the Vietminh Committee was to ensure its 'recognition' by the British authorities as a de facto government. To this end the committee did everything it could to show its strength and demonstrate its ability to 'maintain order'.

Through its press it ordered the dissolution of all the partisan groups that had played an active role in the struggle against Japanese imperialism. All weapons were to be handed over to the Vietminh's own police force. The Vietminh's militia, known as the 'Republican Guard' (Cong hoa-ve-binh) and their police thus had a legal monopoly in the carrying of weapons. The groups aimed at by this decision were not only certain religious sects (the Cao Dai and the Hoa Hao) but also the workers' committees, several of which were armed. Also aimed at were the Vanguard Youth Organisation and a number of 'self-defence groups', many based on factories or plantations. These stood on a very radical social programme but were not prepared to accept complete control by the Vietminh.

The Trotskyists of the Spark group (Tia Sang), anticipating an imminent and inevitable confrontation with the military forces of Britain and France, started to distribute leaflets calling for the formation of Popular Action Committees (tochuc-uy-ban hanh-dong) and for arming of the people. They advocated the creation of a popular assembly, to be the organ of struggle for national independence.

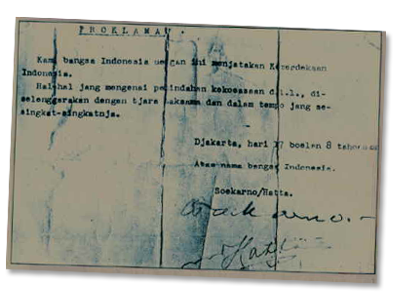

1945 Indonesian Independence

PrintCloseDeclaration by Suharto and Hatta English Translation:

PROCLAMATION WE THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA HEREBY DECLARE THE INDEPENDENCE OF INDONESIA. MATTERS WHICH CONCERN THE TRANSFER OF POWER AND OTHER THINGS WILL BE EXECUTED BY CAREFUL MEANS AND IN THE SHORTEST POSSIBLE TIME. DJAKARTA, 17 AUGUST 1945 IN THE NAME OF THE PEOPLE OF INDONESIA SOEKARNO—HATTA Indonesia War with Dutch (1945-1949)

A Very Useful Summary

1949 Sukarno's Recollections of Independence Achieved

PrintCloseMillions upon millions flooded the sidewalks, the roads. They were crying, cheering, screaming "...Long live Bung Karno..." They clung to the sides of the car, the hood, the running boards. They grabbed at me to kiss my fingers. Soldiers beat a path for me to the topmost step of the big white palace. There I raised both hands high. A stillness swept over the millions. " Alhamdulillah – Thank God," I cried. "We are free".

—Sukarno's recollections of independence achieved

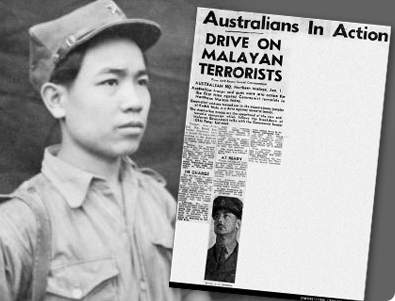

1950 - 1960 The Malayan Emergency

http://www.awm.gov.au/atwar/emergency.asp

PrintCloseThe Malayan Emergency was declared on 18 June 1948, after three estate managers were murdered in Perak, northern Malaya. The men were murdered by guerrillas of the Malayan Communist Party (MCP), an outgrowth of the anti-Japanese guerrilla movement which had emerged during the Second World War. Despite never having had more than a few thousand members, the MCP was able to draw on the support of many disaffected Malayan Chinese, who were upset that British promises of an easier path to full Malayan citizenship had not been fulfilled. The harsh post-war economic and social conditions also contributed to the rise of anti-government activity.

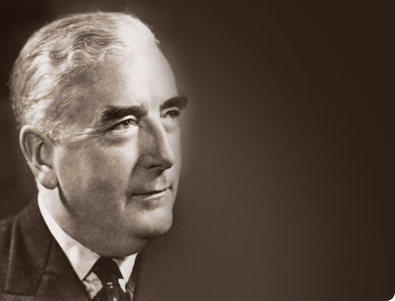

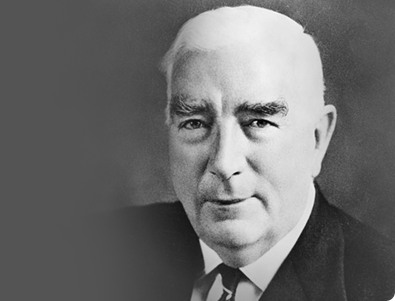

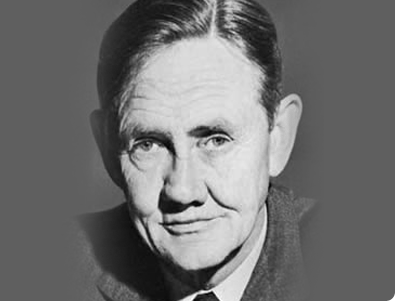

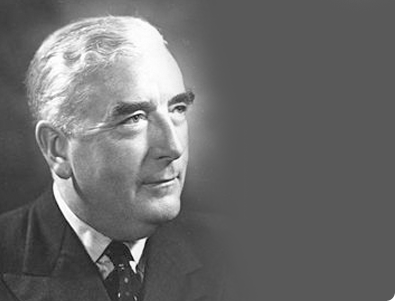

1949 Robert Menzies Begins Second Period as Prime Minister

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/menzies/

PrintCloseRobert Gordon Menzies was Australia's longest serving Prime Minister. He held the office twice, from 1939 to 1941 and from 1949 to 1966. Altogether he was Prime Minister for over 18 years – still the record term for an Australian Prime Minister.

Born into humble circumstances, Menzies obtained a first-class secondary and university education by winning a series of scholarships. He established himself as one of Australia's leading constitutional lawyers, then entered the Victorian parliament in 1928. He won a seat in the federal parliament in 1934 and served as Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the United Australia Party government of Joseph Lyons.

Menzies was Prime Minister when World War II began in 1939. In 1941 he lost the confidence of members of Cabinet and his party and was forced to resign. As an Opposition backbencher during the war years, he helped create the Liberal Party and became Leader of the Opposition in 1946. At the 1949 federal election, he defeated Ben Chifley's Labor Party and once again became Australia's Prime Minister.

Menzies' second period as Prime Minister laid the foundations for 22 consecutive years in government for the Liberal–Country Party Coalition.

Menzies was often characterised as an extreme monarchist and 'British to his bootstraps', but as Prime Minister he maintained Australia's strong defence alliance with the United States. During his second period in office the ANZUS and SEATO treaties were signed, Australian troops were sent to support US-led forces in Korea, and Australia made its first commitment of combat forces to Vietnam.

Menzies retired as Prime Minister and from parliament in 1966. Knighted in 1963, he was further honoured in 1965 by being appointed Constable of Dover Castle and Warden of the Cinque Ports.

Robert Gordon Menzies died on 15 May 1978

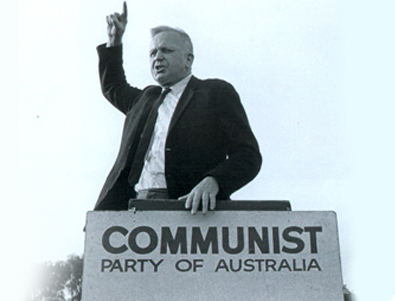

1951 Referendum to Ban Communisim in Australia

PrintCloseReferendum to ban communism in Australia (1951 Australian Referendum was held on 22 September 1951 and sought approval to ban the Communist Party of Australia. It was not carried).

1951 Petrov desertion creates 'spy scare'

PrintCloseIn the book The Petrov Conspiracy Unmasked, the author, J W Brown, states:

The desertion of Vladimir Petrov and his wife from the Soviet Embassy in Australia in April 1951 allowed the Menzies government and the Australian daily newspapers to unleash a spate of 'spy scare' hysteria such as the country had never seen before … [The] truth of the Petrov Affair is that it was no more than a crude political conspiracy organised over a long period with the knowledge of the Prime Minister Robert Gordon Menzies…

The conspiracy was aimed at influencing the 1954 federal elections in favour of the Menzies government. It was further aimed at opening the way for … attacks on both the Communist Party of Australia and the Australian Labor Party.

J W Brown, The Petrov Conspiracy Unmasked, Current Books, Sydney, 1957

1951 ANZUS

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/usmu002.asp

PrintCloseANZUS Treaty signed (1 September 1951, and entered into force on 29 April 1952)

The Parties to this Treaty,

Reaffirming their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all Governments, and desiring to strengthen the fabric of peace in the Pacific Area,

Noting that the United States already has arrangements pursuant to which its armed forces are stationed in the Philippines,(2) and has armed forces and administrative responsibilities in the Ryukyus, and upon the coming into force of the Japanese Peace Treaty may also station armed forces in and about Japan to assist in the preservation of peace and security in the Japan Area,(3)

Recognizing that Australia and New Zealand as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations have military obligations outside as well as within the Pacific Area,

Desiring to declare publicly and formally their sense of unity, so that no potential aggressor could be under the illusion that any of them stand alone in the Pacific Area, and

Desiring further to coordinate their efforts for collective defense for the preservation of peace and security pending the development of a more comprehensive system of regional security in the Pacific Area,

Therefore declare and agree as follows:

ARTICLE I

The Parties undertake, as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations, to settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

ARTICLE II

In order more effectively to achieve the objective of this Treaty the Parties separately and jointly by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.

ARTICLE III

The Parties will consult together whenever in the opinion of any of them the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the Parties is threatened in the Pacific.

ARTICLE IV

Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.

Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall be immediately reported to the Security Council of the United Nations. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.

ARTICLE V

For the purpose of Article IV, an armed attack on any of the Parties is deemed to include an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of any of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific or on its armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific.

ARTICLE VI

This Treaty does not affect and shall not be interpreted as affecting in any way the rights and obligations of the Parties under the Charter of the United Nations or the responsibility of the United Nations for the maintenance of international peace and security.

ARTICLE VII

The Parties hereby establish a Council, consisting of their Foreign Ministers or their Deputies, to consider matters concerning the implementation of this Treaty. The Council should be so organized as to be able to meet at any time.

ARTICLE VIII

Pending the development of a more comprehensive system of regional security in the Pacific Area and the development by the United Nations of more effective means to maintain international peace and security, the Council, established by Article VII, is authorized to maintain a consultative relationship with States, Regional Organizations, Associations of States or other authorities in the Pacific Area in a position to further the purposes of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of that Area.

ARTICLE IX

This Treaty shall be ratified by the Parties in accordance with their respective constitutional processes. The instruments of ratification shall be deposited as soon as possible with the Government of Australia, which will notify each of the other signatories of such deposit. The Treaty shall enter into force as soon as the ratifications of the signatories have been deposited.

ARTICLE X

This Treaty shall remain in force indefinitely. Any Party may cease to be a member of the Council established by Article VII one year after notice has been given to the Government of Australia, which will inform the Governments of the other Parties of the deposit of such notice.

ARTICLE XI

This Treaty in the English language shall be deposited in the archives of the Government of Australia. Duly certified copies thereof will be transmitted by that Government to the Governments of each of the other signatories.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF the undersigned Plenipotentiaries have signed this Treaty.

DONE at the city of San Francisco this first day of September, 1951.

(1) TIAS 2493; 3 UST 3423-3425. Ratification advised by the Senate, Mar. 20, 1952, ratified by the President, Apr.15, 1952; entered into force, Apr. 29, 1952.

(2) A Decade of American Foreign Policy, pp. 881-885 and 869-881.

(3) See article 6 of the Japanese peace treaty (extra, p. 428) and the security treaty with Japan.

1954 Petrov Affair

http://moadoph.gov.au/exhibitions/online/petrov/royal-commission.html

PrintClosePetrov Affair (a dramatic Cold War spy incident in Australia in April 1954, concerning Vladimir Petrov, Third Secretary of the Soviet embassy in Canberra.1951)

On April 13, the eve of the last Parliamentary sitting day before the 1954 election campaign, Prime Minister Robert Menzies announced the defection of Vladimir Petrov. He called for a Royal Commission to investigate evidence of espionage contained in the documents Petrov brought with him.

Leader of the Opposition, H V Evatt came to believe that the Petrov defections were part of a sinister conspiracy devised by Menzies, ASIO and Catholic anti-communist elements inside the Labor Party to secure a Coalition victory at the 1954 election. Members of Evatt's staff had been named in the Petrov documents. He claimed they were forgeries sold by Petrov to the government to damage the Labor Party. He took his case to the Royal Commission.

On September 7 1954, after a series of extraordinary outbursts the Commissioners withdrew Evatt's leave to appear before the Royal Commission. They argued that he was representing his own political interests as Leader of the Opposition and not his clients' interests. Evatt's suspicion of a conspiracy deepened as a result of his dismissal.

The final report of the Royal Commission was released on September 14 1955. It concluded that the Petrov documents were genuine and that the Petrovs were 'witnesses of truth'. However no prosecutions were recommended as a result of the inquiry. Although the Commission cast suspicion on six men – Fergan O'Sullivan, Rupert Lockwood, Frances Bernie, Ian Milner, Jim Hill and Walter Clayton – there was no existing Australian law covering their alleged crimes. In the case of Milner and Hill the Commission's judgement rested on evidence that could not have been produced in court—the results of a top-secret code breaking operation.

1962 West New Guinea Issue

PrintCloseFrankly, there is very little information about West New Guinea even from official versions, except that West New Guinea was a part of the Netherlands East Indies and was retained by the Dutch after the transfer of sovereignty to the Republic of Indonesia on 27th December 1949. After the constant agitation by the Republic of Indonesia to acquire West New Guinea, the Netherlands was forced to turning it over to the control of the United Nations on 15 August 1962. On 1st May 1963, the United Nations turned it over to the Republic of Indonesia, which created it the province of West Irian.

Although the official version of West New Guinea is somewhat "with nothing to say", the US/CIA documents tell a lot. Before we have further discussion, please remember two things:

1. On 5 March 1960 President Sukarno dissolved Parliament ('DPR') which was the result of an election on 29th September 1955 and created a new parliament ('DPRDG'). More importantly, Masyumi, a non-communist party which held 21% seats in 'DPR', was banned because of its involvement during the PRRI/Permesta Rebelion; and PKI gained more political strength in Indonesian politics.

President Sukarno launched a military campaign against the Dutch over West New Guinea on 18th December 1961

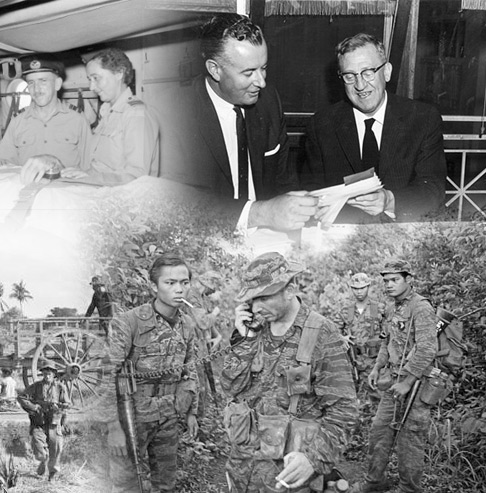

1962 Australian Involvement

PrintCloseIn the early 1960s South Vietnam was a land beset by problems. The government was under threat from a growing communist insurgency, losing control over the countryside outside major towns and cities and facing internal dissent. The South Vietnamese government sought assistance from the United States and her regional ally, Australia. Both countries responded with civil and military aid. Australia's contribution was small in comparison to America's, but sufficient to show loyalty to the United States, Australia's most valued ally. The United States was keen to avoid the appearance of replacing French colonialism with American imperialism, and the involvement of other countries from the region, such as Australia, helped avoid this perception by suggesting a more international approach.

Australia's initial military contribution to South Vietnam was modest; comprising a team of 30 advisers who worked in various areas of the country under the command of Colonel F.P. 'Ted' Serong. Known as the Australian Army Training Team Vietnam (AATTV), they gave Australia a presence in South Vietnam and were seen as an embodiment of the Australian doctrine of 'Forward Defence' - meeting threats at their source rather than waiting to fight an enemy on Australian soil.

Colonel F P (Ted) Serong arrived in Saigon, South Vietnam's capital, on 31 July 1962. His men followed on 3 August. This small unit was the vanguard of Australia's decade-long involvement in the Vietnam War.

Australia Sends Advisers to Vietnam

24 May 1962

PrintCloseFormal announcement that Australia would send 30 military advisers to South Vietnam. This was the largest commitment by any nation to South Vietnam other than the USA at that time. In 1964 the situation remained unchanged regarding countries commited to supporting South Vietnam with military personnel.

1965 Arthur Calwell opposes Australia's commitment of troops to South Vietnam

PrintCloseFive days(May 4, 1965), after the Prime Minister's announcement the Leader of the Opposition in the House of Representatives, Arthur Calwell, spoke in Parliament, opposing Australia's commitment of troops to South Vietnam.

Our men will be fighting the largely indigenous Viet Cong in their own home territory. They will be fighting in the midst of a largely indifferent, if not resentful, and frightened population. They will be fighting at the request of, and in support, and, presumably, under the direction of an unstable, inefficient, partially corrupt military regime which lacks even the semblance of being, or becoming, democratically based.

It is also true that there were some people who opposed the war from the start and believed that it was of no concern to Australia. Opposition Leader Arthur Calwell represented this view right from the start of Australia's involvement:

'We do not think it is a wise decision. We do not think it is a timely decision. We do not think it will help the fight against Communism. On the contrary, we believe it will harm that fight in the long term. We do not believe it will promote the welfare of the people of Vietnam. On the contrary, we believe it will prolong and deepen the suffering of that unhappy people so that Australia's very name may become a term of reproach among them. We do not believe that it represents a wise or even intelligent response to the challenge of Chinese power. On the contrary, we believe it mistakes entirely the nature of that power, and that it materially assists China in her subversive aims. Indeed, we cannot conceive a decision by the Government more likely to promote the long term interests of China in Asia and the Pacific.'

1965 Australia to send own army to Vietnam

- Menzies

PrintCloseOn 29 April 1965 the Prime Minister, Robert Menzies, made a statement on Vietnam to a half-empty House of Representatives. At eight o'clock at night he announced the extension of Australian commitment in Vietnam both militarily and economically. After three years of providing military advisors to help train the Army of the Republic of Vietnam, Australia was now to send its own army into the South East Asian country in the form of an infantry Battalion (soldiers who fought on foot).

The Australian Government is now in receipt of a request from the Government of South Vietnam for further military assistance. We have decided - and this has been done after close consultation with the Government of the United States - to provide an infantry battalion for service in South Vietnam…. The takeover of South Vietnam would be a direct military threat to Australia and all the countries of South and South-East Asia.Excerpt from Prime Minister Robert Menzies' speech in Parliament, 29 April 1965

This speech did not look like the beginning of the biggest ever deployment of Australian troops outside the two world wars. The rather low key announcement underplayed the extent of Australia's eventual involvement. Like the USA, Australia got slowly drawn in to what was essentially a civil war and a nationalist battle for independence. The Vietnam War never fulfilled any of its promise as a heroic battle against the evils of communism that the US and Australia thought it would.

The first troops

In 1962, after requests from the US and the Republic of Vietnam (RVN), Australia had sent in 30 military advisors to assist with the training of the RVN Army. These advisors were highly skilled in jungle warfare. They had been involved in the confrontation with Indonesia and had learned from Australian action in the jungles during World War Two. A Royal Australian Air Force squadron was also posted to nearby Thailand to act as back up.

By 1964, it was clear that the South Vietnamese forces would be beaten by the combined efforts of the Viet Cong and North Vietnam. If nothing was done, the South Vietnamese democracy (such as it was) would fall into communist hands. America began sending in more troops and asked for more countries to become actively involved so it would not seem like just an American action, but a group of countries helping out a beleaguered democracy. In June, Australia responded to the 'more international flags in Saigon' campaign and upped the number of its advisors to 60. By 1965 that number rose again to over 100, and, of course, by April the infantry battalion announced by Menzies in parliament was on its way. The Vietnam War had begun in earnest and so had Australia's participation in it.

The 1st Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (RAR), consisting of 778 soldiers, arrived in Vietnam in May 1965. These were career soldiers, men who had chosen a job in the army - conscripts were not sent until the next year. Conscription had been re-introduced to Australia in November 1964. It was called the National Service Scheme and required all men to register when they turned 20. Each year certain dates were drawn and those whose birthdays were on that date (and who passed the medical and educational tests) had to serve in the army for two years. Anyone who did not fulfil their National Service obligations without a good reason could be fined or imprisoned. The first army units containing National Service conscripts entered the Vietnam War in early 1966.

Involvement in the War is Necessary - Hasluck

(Menzies Government Minister Hasluck, 1966)

PrintCloseHowever, many people genuinely believed that our involvement in the war was necessary because the war in Vietnam did affect Australia directly - it was our war. This can be seen in, for example, the Prime Minister's speech committing Australians, and in the attitude of some of the soldiers involved:

'There can be no doubt of the gravity of the situation in South Vietnam. There is ample evidence to show that with the support of the North Vietnamese regime and other Communist powers, the Viet Cong has been preparing on a more substantial scale than ... (before) insurgency action designed to destroy South Vietnamese government control, and to disrupt by violence the life of the local people ... The takeover of South Vietnam would be a direct military threat to Australia and all the countries of South and South-East Asia. It must be seen as part of a thrust by Communist China between the Indian and Pacific Oceans.' 'Behind Vietnam lies a wider conflict that extends from the northern frontiers of India to the dividing line in Korea; that engages the world wide diplomacy of the United States; and that casts a shadow of fear over millions of people in all lands of southern Asia no less than the shadow of terror over the villagers of the Mekong delta. This is a war that affects the fate of all countries of South-east Asia -- a war that throws into sharp relief the aim of Communist China to dominate them by force.'

1966 "I Subscribe to the Domino Theory"

- Menzies

PrintClose'I subscribe to the domino theory ... because I believe it obvious ... that if the Vietnam War ends with some compromise that denies South Vietnam a real and protected independence, Laos and Cambodia, Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia will be vulnerable ... this domino theory ... has formidable reality to Australians who see the boundaries of aggressive communism coming closer and closer.'

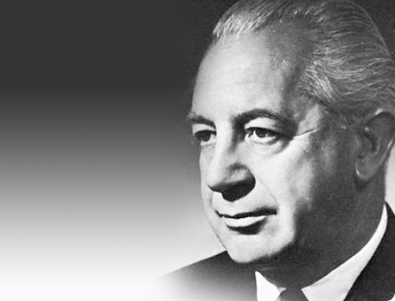

June 1966 Prime Minister Holt Announces "All the way with LBJ"

PrintCloseOn taking office, Holt declared that Australia had no intention of increasing its commitment to the war, but just one month later, in December 1966, he announced that Australia would treble its troop commitment to 4,500, including 1,500 National Service conscripts, creating a single independent Australian task force based at Nui Dat.

Five months later, in May, Holt was obliged to announce the death of the first National Service conscript in Vietnam, Private Errol Wayne Noack, aged 21. Just before his disappearance, Holt approved a further increase in troop numbers, committing a third battalion to the war—a decision that was subsequently revoked by his successor, John Gorton.

Holt visited the USA in late June 1966, where he gave a speech in Washington in the presence of President Johnson. Reported in The Australian on 1 July 1966, Holt's speech concluded with a remark which has come to be seen as encapsulating his unquestioning support for Johnson, for America's Vietnam policy and for continued Australian military involvement in the Vietnam War:

"You have in us not merely an understanding friend but one staunch in the belief of the need for our presence in Vietnam.…

"We are not there because of our friendship, we are there because, like you, we believe it is right to be there and, like you, we shall stay there as long as it seems necessary to achieve the purposes of the South Vietnamese Government and the purposes that we join in formulating and progressing together.

"And so, sir, in the lonelier and perhaps even more disheartening moments which come to any national leader, I hope there will be a corner of your mind and heart which takes cheer from the fact that you have an admiring friend, a staunch friend that will be all the way with LBJ."

1966 Australia's 17th Prime Minister Harold Holt

(in office 26 January 1966 – 17 December 1967)

PrintCloseHolt's tenure fell during one of the hottest periods of the Cold War era, and his government faced some unenviable foreign policy challenges. Global political, commercial and military alignments were rapidly reconfigured as the Soviets and the USA vied for world domination in diverse theatres of conflict. Australia's ties with the UK dwindled rapidly as Britain closed foreign bases, disengaged from its former territories East of Suez and began courting the EEC, as a result of which American investment in Australia skyrocket and Australia's onetime enemy Japan take over from the UK as Australia's major trading partner.

Strategically, the period was dominated by Lyndon Johnson's fateful decision to escalate the war in South East Asia. Australia's involvement in Vietnam increased significantly under Holt, with Australian troops fighting and dying in sometimes desperate battles like Long Tan. Growing community unrest about the draft, the rising tide of casualties and social debate about the moral rectitude of the war fuelled the first significant stirrings of organised domestic opposition, such as the influential community anti-conscription organisation Save Our Sons.

1967 John McEwan becomes Prime Minister after death of Holt

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/mcewen/

PrintCloseJohn McEwen was Prime Minister from 19 December 1967 to 10 January 1968 following the death of Harold Holt. His term as Prime Minister came near the end of his 37 years in parliament.

Though only briefly Prime Minister, McEwen served as deputy Prime Minister for twelve years, in the governments of Robert Menzies, Harold Holt and John Gorton. He was acting Prime Minister many times in the years from 1958 to 1971. McEwen held the key ministerial responsibilities of Commerce and Trade for 20 years from 1949 to 1971. During this time the portfolio emphasis moved away from agriculture and into the broader industry area. Though a farmer and Country Party leader, McEwen also moved the emphasis from low tariffs to protection of manufacturing industries.

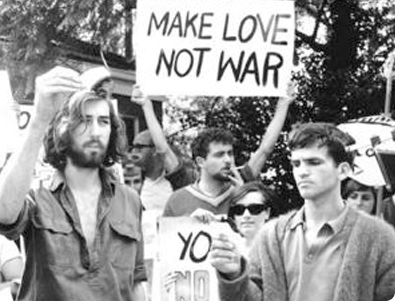

Late 1960's Anti-Vietnam War Protests

http://www.camden-h.schools.nsw.edu.au/pages/Faculties/History/yr10topics/antiviet.htm

PrintCloseLate 1960s and early 1970s were a time that saw the rise of protest movements across Australia. Causes included: Opposition to the Vietnam War, Racial equality, Equal rights for women and Environmental protection

Protest was not simply between generations ie the young and the old, it was more complex.

First protests were small and non-violent. They were organised by already established anti-war movements. They were made up of middle aged and middle class people and young radicals who favoured extreme change.

Church leaders were divided. Reverend Allan Walker of the Methodist Central Mission in Sydney was a leading critic.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) was divided eg in 1965 it passed a resolution expressing concern rather than taking industrial action.

Forms of Protest

- Teach-ins took place from 1965. Speakers holding a variety of opinions debated the issues. Leading speakers against the war included Dr Jim Cairns, a Shadow Minister in the Labor Opposition in Federal Parliament and Morris West, a prominent author and influential Roman Catholic.

- The Youth Campaign Against Conscription (YCAC) – university students who organised marches and demonstrations.

- Save Our Sons(SOS) movement (1965) largely middle-aged women held silent protest vigils.

- Seamen's Union in 1965 refused to carry war materials to Vietnam.

- From 1966 protests became more radical. Young men burned their draft cards and protests saw clashes between the demonstrators and the police.

- Some young men decided to go to jail rather than be conscripted. The courts could exempt those who could prove they were pacifists (opposed to all wars on religious or moral grounds).

Grounds for opposition to the Vietnam War

- It was believed that Australians were being sent to fight for an unpopular and corrupt dictatorship.

- It was a civil war and we had no business being there.

- It was immoral to send young conscripts who were too young to vote. You had to be 21 at that time to vote.

- Television coverage showed the horrors of war eg use of napalm, execution of old people, women and children. Famous image of Saigon's Police Chief executing a Viet Cong dead in the street.

- Fire free zones – places where Vietnamese villages were bombed ad machined gunned without restriction.

- "Mai Lai Massacre" in 1968 where 120 Vietnamese were slaughtered shocked the world.

- The question was, "Did we have to kill them, in order to save them? Could they have been any worse off under communism?"

The Final Stages

Protests increased and became more directed towards symbols of the United States in Australia.

Public opinion began to change in August 1969 55% of Australians favoured withdrawing the troops.

During 1970 and 1971 huge public protests called the Vietnam Moratoriums (stop the war) saw hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets in protest.

These protest finished when Gough Whitlam and his Labor Government were elected in 1972 on a promise to bring home the troops. (By this time most had already come home).

Key terms: Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), Teach-ins, Youth Campaign Against Conscription (YCAC), Save Our Sons(SOS), Seamen's Union , corrupt dictatorship, civil war, 'Fire free zones', "Mai Lai Massacre", Vietnam Moratoriums.

1968 John Gorton becomes Prime Minister

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/gorton/

PrintCloseOn 10 January 1968, John Gorton became the 19th Prime Minister in unusual circumstances. He was elected Liberal Party leader to replace Harold Holt, who had disappeared the previous month while swimming off the Victorian coast, and was presumed dead. Gorton also left the job in unusual circumstances – he declared himself out of office after a tied party vote of confidence in his leadership on 10 March 1971.

A determined non-conformist and a passionate Australian nationalist, Gorton wanted to turn thinking in the party, and in the nation, in a more independent direction.

1968 - 1971 Defence and Foreign Policy - John Gorton

Prime Minister John Gorton with Indonesian President Soeharto in Djakarta during the Gorton's visit in 1968. NAA: A1200, L73540

PrintCloseDuring Gorton's term as Prime Minister defence was a compelling national issue. The Gorton government inherited Australia's commitment to the war in South Vietnam and to the defence of Malaysia and Singapore from Communist insurgents. Gorton himself was ambivalent about what was then called 'forward defence'. He opposed any increase in the size of the Australian contingent in South Vietnam above the 8000 already there. In his view, Australia would be better and less expensively served by building a mobile force based on Australian soil.

At the end of 1970, the Gorton government began the Australian withdrawal from South Vietnam when it did not replace the 8th Battalion when it ended its tour of duty. This was by no means a clear decision. With army chiefs hostile to any hint of withdrawal, Cabinet reached the decision reluctantly and against army advice. The army's Cabinet submission in response was, in the view of one senior official, 'argumentative, impudent and wilful'.

Gorton also rejected any open-ended commitment to Malaysia and Singapore. He advocated a physical presence in the region in order to ensure American and British support in the event of further Communist expansion or general instability. The 'Five Power' arrangement represented the growing interest of Australia and New Zealand in Malaysia and Singapore, and the receding interest of Britain. It was a delicate situation where Gorton had to balance his preference for an independent policy with the need to maintain a partnership with Australia's traditional 'great and powerful friends'. He did not achieve the desired balance, but he did establish a good working relationship with the administration of US President Richard Nixon, and with both a Labour and a Conservative government in Britain.

1970 Australia withdraws from Vietnam War

PrintCloseBy late 1970 Australia had also begun to wind down its military effort in Vietnam. The 8th Battalion departed in November (and was not replaced), but, to make up for the decrease in troop numbers, the Team's strength was increased and its efforts became concentrated in Phuoc Tuy province. The withdrawal of troops and all air units continued throughout 1971 – the last battalion left Nui Dat on 7 November, while a handful of advisers belonging to the Team remained in Vietnam the following year. In December 1972 they became the last Australian troops to come home, with their unit having seen continuous service in South Vietnam for ten and a half years.

Australia's participation in the war was formally declared at an end when the Governor-General issued a proclamation on 11 January 1973. The only combat troops remaining in Vietnam were a platoon guarding the Australian embassy in Saigon (this was withdrawn in June 1973).

1971 McMahon Announces Further Reductions

http://www.vietvet.org/aussie1.htm/

PrintCloseOn March 30, 1971, the new Prime Minister, Mr. McMahon, announced, inter alia, that.......due to the satisfactory progress towards the objecti- ve of establishing the circumstances in which South Vietnam could determine it's own future, the Government had decided that further reductions of the Australian forces in Vietnam were feasible and desirable.

The reduction was made gradually over a period of four to six months commencing in May 1971. Spread over the three Services it had the effect of reducing the total Australian personnel by about 1000 men. The force remaining comprised 6000 men compared with a peak of 8000 in 1968-70.

Those withdrawn were:

- Selected combat and supporting forces of the Army task force, including the tank squadron, totalling about 650 men;

- Royal Australian Navy personnel, about 45 in number, serving with the United States Assault Helicopter Company;

- The RAN Clearance Diving Team ( clearance of underwater explosives ) of 6 personnel;

- No.2 Canberra Bomber Squadron involving 280 men; some aircraft of the Caribou transport squadron and about 44 men.

Out by Christmas

The Prime Minister announced on the 18th August 1971 that the bulk of Australia's combat troops would be withdrawn by Christmas 1971. Planning and preparation, both in Australia and Vietnam proceeded rapidly to handle the immense task of bringing home the thousands of men and varieties of equipment, as well as handing over to the Vietnamese forces the responsibilities of the !st Australian Task Force.

The 3rd Battalion, R.A.R., arriving home in October 1971 and early in November 1971, the remaining elements of the 1st Australian Task Force moved from their base in Nui Dat to the coastal logistic base at Vung Tau.

The last remaining major combat unit to leave Vietnam - the 4th Battalion, R.A.R. - arrived back in Australia on 17th December 1971. They arrived on board the RAN fast transport, HMAS Sydney, with the 104th Field Artillery Battery and airmen and helicopters of No.9 Squadron, RAAF.

Remaining elements were to come home by the early months of 1972 after the preparation and packing of stores for return to Australia or for hand over to the South Vietnamese authorities.

1972 Australia's Foreign Policy

- Gough Whitlam

PrintCloseChanges in Foreign Policy

- Wanted to distance Australia from military commitment in Vietnam.

- Withdrew Australia from the Vietnam War and ended conscription.

- Granted PNG self-government in 1973 and independence in 1975.

- Encouraged involvement or support for international agreements on environmental, heritage and human rights issues.

- Greater active participation in the UN, such as signing conventions.

- Wanted to establish Australia as an independent nation (away from USA and UK)

- Took initiatives to improve relations with communist nations such as China, East Germany, North Vietnam and North Korea. Whitlam

1971 William McMahon elected as Prime Minister

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/mcmahon/

PrintCloseWilliam McMahon was Prime Minister from 1971 to 1972. He was first elected to parliament in 1949, and held the seat of Lowe, in Sydney, for 33 years until his retirement in 1982.

McMahon served as Minister for Primary Industry (1956–58) and Minister for Labour and National Service (1958–66) in the government of Robert Menzies, as Treasurer (1966–69) in the governments of Harold Holt, John McEwen and John Gorton, and as Minister for External Affairs (1969–71) in the Gorton government.

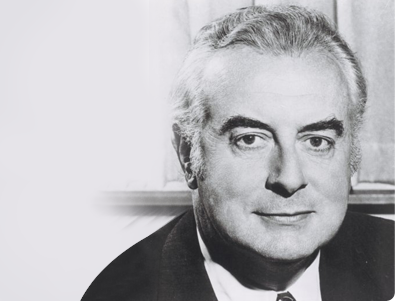

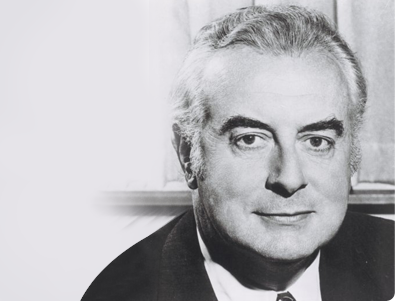

1972 Gough Whitlam Australia's 21st Prime Minister

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/whitlam/

PrintCloseGough Whitlam became Australia's 21st Prime Minister on 5 December 1972. His Labor government, the first after more than two decades, set out to change Australia through a wide-ranging reform program. Whitlam's term abruptly ended when his government was dismissed by the Governor-General on 11 November 1975.

The public lives of Gough Whitlam and his wife Margaret extend over half a century. After serving in the Royal Australian Air Force, Whitlam joined the Australian Labor Party in 1945. He became the Member for Werriwa in Sydney's south in 1952, retaining the seat in 11 more federal elections over the next 25 years.

Whitlam led the reform of the Labor Party platform during the long years in Opposition. As Prime Minister he immediately set about implementing a reform program that included strengthening Australia's status by making Queen Elizabeth II Queen of Australia. His government drew on international agreements to develop programs on human rights, the environment and conservation.

Margaret Whitlam played an important role as a political and prime ministerial wife. An outspoken public speaker, broadcaster and columnist, she accompanied Gough Whitlam on his countless overseas travels. As a qualified social worker, she was particularly interested in social conditions. Their public lives have continued since they left The Lodge in 1975.

1975 Malcolm Fraser Elected as Prime Minister

http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/fraser/

PrintCloseMalcolm Fraser was Australia's 22nd Prime Minister. He began his term as caretaker Prime Minister on 11 November 1975, after Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Gough Whitlam's Labor government. The Fraser Coalition government was returned with the largest landslide of any federal election a month later, and remained in office until 1983. Nonetheless, the constitutional crisis made its beginning controversial and marked Fraser's prime ministership.

Malcolm Fraser had an important influence on the changing relations of countries within the British Commonwealth, and on shaping Australia's relations with the countries of East and Southeast Asia. Though economic rationalism was introduced in policy debate during his term of office, his government reflected more traditional principles in financial management and fiscal policy.

Before becoming Prime Minister, Malcolm Fraser had spent ten years as a backbencher in the government of Robert Menzies. He became Minister for the Army in 1966, under Harold Holt, and was also a minister in the governments of John Gorton and William McMahon.

1975 Vietnam Was Not Just About Fulfilling Alliance Commitments

- Lyndon Baines Johnson

PrintCloseAustralia's commitment to the US in Korea and Vietnam was not just about fulfilling Alliance commitments but ensuring that America was drawn into the South East Asian Area. Given the proximity to Australia of an unstable Indonesia, with pro Communist elements, Gareth Evans, future Labor foreign minister said; "The Australian desire to see the United States actively engaged in the security of South East Asia was ..understandable."

"That old arm twister, Lyndon Baines Johnson, did not, as is the widely held belief, force Australia into the war in April 1965. Indeed, documents in the US archives confirm that, when America appeared to be wavering early that year on whether to commit ground troops, Australia applied pressure to involve the US more heavily in the war."The National Times 1975

Election Results and Public Opinion Polls

PrintCloseDid Australians strongly oppose involvement in the Vietnam War?

Examine these election results. In each case the Vietnam War was a major issue.

Party House of Representatives Senate 1963 1966 1969 1972 1966 1969 Liberal 52 61 46 38 23 21 21 Country Party 20 21 20 20 7 7 5 ALP 52 41 59 58 27 27 26 DLP - - - - 2 4 5 Indep - 1 - - 1 1 3 Now examine the results of public opinion polls (published in Peter Cook, Australia and Vietnam 1965 - 1972, La Trobe University Melbourne, 1991 page 39).

Poll date Sept 65 Sept 66 May 67 Oct 68 Dec 68 Apr 69 Aug 69 Oct 69 Oct 70 Continue to fight (%) 56 61 62 54 49 48 40 39 42 Bring back (%) 28 27 24 38 37 40 55 51 50 Undecided 16 12 14 8 14 12 6 10 8

Anti-Vietnam War Protests

http://www.camden-h.schools.nsw.edu.au/pages/Faculties/History/yr10topics/antiviet.htm

PrintCloseLate 1960s and early 1970s were a time that saw the rise of protest movements across Australia. Causes included: Opposition to the Vietnam War, Racial equality, Equal rights for women and Environmental protection.

Protest was not simply between generations ie the young and the old, it was more complex.

First protests were small and non-violent. They were organised by already established anti-war movements. They were made up of middle aged and middle class people and young radicals who favoured extreme change.

Church leaders were divided. Reverend Allan Walker of the Methodist Central Mission in Sydney was a leading critic.

The Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU) was divided eg in 1965 it passed a resolution expressing concern rather than taking industrial action.

Forms of Protest

- Teach-ins took place from 1965. Speakers holding a variety of opinions debated the issues. Leading speakers against the war included Dr Jim Cairns, a Shadow Minister in the Labor Opposition in Federal Parliament and Morris West, a prominent author and influential Roman Catholic.

- The Youth Campaign Against Conscription (YCAC) – university students who organised marches and demonstrations.

- Save Our Sons(SOS) movement (1965) largely middle-aged women held silent protest vigils.

- Seamen's Union in 1965 refused to carry war materials to Vietnam.

- From 1966 protests became more radical. Young men burned their draft cards and protests saw clashes between the demonstrators and the police.

- Some young men decided to go to jail rather than be conscripted. The courts could exempt those who could prove they were pacifists (opposed to all wars on religious or moral grounds).

Grounds for opposition to the Vietnam War

- It was believed that Australians were being sent to fight for an unpopular and corrupt dictatorship.

- It was a civil war and we had no business being there.

- It was immoral to send young conscripts who were too young to vote. You had to be 21 at that time to vote.

- Television coverage showed the horrors of war eg use of napalm, execution of old people, women and children. Famous image of Saigon's Police Chief executing a Viet Cong dead in the street.

- Fire free zones – places where Vietnamese villages were bombed ad machined gunned without restriction.

- "Mai Lai Massacre" in 1968 where 120 Vietnamese were slaughtered shocked the world.

- The question was, "Did we have to kill them, in order to save them? Could they have been any worse off under communism?"

The Final Stages

Protests increased and became more directed towards symbols of the United States in Australia.

Public opinion began to change in August 1969 55% of Australians favoured withdrawing the troops.

During 1970 and 1971 huge public protests called the Vietnam Moratoriums (stop the war) saw hundreds of thousands of people take to the streets in protest.

These protest finished when Gough Whitlam and his Labor Government were elected in 1972 on a promise to bring home the troops. (By this time most had already come home).

Key terms: Australian Council of Trade Unions (ACTU), Teach-ins, Youth Campaign Against Conscription (YCAC), Save Our Sons(SOS), Seamen's Union , corrupt dictatorship, civil war, 'Fire free zones', "Mai Lai Massacre", Vietnam Moratoriums.

Australia's Involvement in the Vietnam War, the Political Dimension

© Brian Ross, 1995

PrintCloseWhy Australia became involved in the Vietnam War:

The reasons as to why Australia became involved in the Vietnam War have been traditionally painted in the colours of "collective security" and as part of the anti-Communist "crusade" to contain a world wide communist threat. However, the decision to become involved was not one take in isolation by the government of the day in Canberra. Rather it was the culmination of a long period of tension and unease, not as one might believe, over the idea of communist expansionism in Asia, but rather because of what was considered the unsatisfactory relationship which had developed between Canberra and Washington. The key to that relationship had been Indonesia and its relations with Australia over first Dutch West New Guinea (now Irian Jaya) and then Malaysia. Indeed as Greg Pemberton points out, "Australia's defence and foreign policy during the post war period cannot be fully understood without reference to Indonesia..."

Advice Given to Australian Government by its Ambassador to Washington

PrintCloseOne of the reasons given by Prime Minister Menzies in committing Australian combat troops to Vietnam was that we would thereby be fulfilling a commitment not to Vietnam, but to the United States, which needed support for its involvement in the war.

This can be seen in the advice given to the Australian government by its Ambassador to Washington:

'Our objective should be ... to achieve such an habitual closeness of relations with the United States and sense of mutual alliance that in our time and need, after we have shown all reasonable restraint and good sense, the United States would have little option but to respond as we would want.'

'The problem of Vietnam is one, it seems, where we could ... pick up a lot of credit with the United States, for this problem is one to which the United States is deeply committed and in which it genuinely feels it is carrying too much of the load, not so much the physical load the bulk of which the United States is prepared to bear, as the moral load.'

Australian Casualties in the Vietnam War, 1962 - 72

http://www.awm.gov.au/encyclopedia/vietnam/statistics.asp

PrintCloseThese statistics were sourced from the appendix of On the offensive: the Australian Army in the Vietnam War 1967–1968. For details of the total number of Australians who died during the Vietnam War, 1962- 1975, please refer to Deaths as a result of service with Australian units.

Statistics: Total Australian service casualties in the Vietnam War, 1962–72

Service Army RAN RAAF TOTAL Died 478 8 14 500 Wounded/injured/ill 3,025 48 56 3,129 Total 3,505 56 70 3,629 Note: The total of 500 deaths comprises 426 battle casualties and 74 non-battle casualties.

Australian Army casualties in the Vietnam War, 1962-1972

Battle casualties

Killed in action Killed accidentally Died of wounds Died of injury/illness Missing presumed dead Drowned Wounded in action Wounded accidentally Injured/ill in battle Australian Regular Army 172 15 40 0 0 1 1,140 92 79 National Servicemen 143 10 28 3 1 0 880 87 63 Citizen's Military Forces 1 0 0 0 0 0 6 1 0 Total 316 25 68 3 1 1 2,026 180 142

Totals by category

414 killed in battle, 2,348 wounded in battle

Non-battle casualties

Killed/died Injured/ill Australian Regular Army 49 426 National Servicemen 15 249 Citizen's Military Forces 0 2 Total 64 677

Australian Army casualties in Vietnam by year, 1962–72

BC = Battle casualty

NBC = Non-battle casualty

Deaths

Year 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 Total BC 0 0 1 11 56 70 102 95 54 28 0 417 NBC 0 1 0 5 7 11 5 9 11 12 0 61 Total 0 1 1 16 63 81 107 104 65 40 0 478

Wounded/injured/ill

Year 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 Total BC 0 0 8 83 226 276 529 648 422 166 4 2,362 NBC 2 1 1 17 62 131 170 145 69 60 5 663 Total 2 1 9 100 288 407 699 793 491 226 9 3,025

Source

Appendix F, "Statistics", Ian McNeil and Ashley Ekins, On the offensive: the Australian Army in the Vietnam War 1967–1968 (Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin, 2003)

Australia in Vietnam War - Overview

http://vietnam-war.commemoration.gov.au/vietnam-war/index.php

PrintCloseThe Vietnam War was the longest major conflict in which Australians have been involved; it lasted ten years, from 1962 to 1972, and involved some 60,000 personnel. A limited initial commitment of just 30 military advisers grew to include a battalion in 1965 and finally, in 1966, a task force. Each of the three services was involved, but the dominant role was played by the Army.

In the early years Australia's participation in the war was not widely opposed. But as the commitment grew, as conscripts began to make up a large percentage of those being deployed and killed, and as the public increasingly came to believe that the war was being lost, opposition grew until, in the early 1970s, more than 200,000 people marched in the streets of Australia's major cities in protest.

By this time the United States Government had embarked on a policy of 'Vietnamisation' - withdrawing its own troops from the country while passing responsibility for the prosecution and conduct of the war to South Vietnamese forces. Australia too was winding down its commitment and the last combat troops came home in March 1972. The RAAF, however, sent personnel back to Vietnam in 1975 to assist in evacuations and humanitarian work during the war's final days. Involvement in the war cost more than 500 Australian servicemen their lives, while some 3,000 were wounded, otherwise injured or were victims of illness.

The South Vietnamese fought on for just over three years before the capital, Saigon, fell to North Vietnamese forces in April 1975, bringing an end to the war which by then had spilled over into neighbouring Cambodia and Laos. Millions lost their lives, millions more were made refugees and the disaster that befell the region continues to reverberate today. For Australia the Vietnam War was the cause of the greatest social and political dissent since the conscription referenda of the First World War.

Labor and Vietnam: A Reappraisal

Ashley Lavelle*

PrintCloseArguing from a Marxist perspective, this paper maintains that the shift in the Australian Labor Party's (ALP) Vietnam War policy in favour of withdrawal of Australian troops from Vietnam was largely brought about by pressure from the Anti-Vietnam War Movement (AVWM) and changing public opinion, rather than being a response to a similar shift by the United States government, as some have argued. The impact of the AVWM on Labor is often understated. This impact is indicated not just by the policy shifts, but also the anti-war rhetoric and the willingness of Federal Parliamentary Labor Party (FPLP) members to support direct action. The latter is a particularly neglected aspect of commentary on Labor and Vietnam. Labor's actions here are consistent with its historic susceptibility to the influence of radical social movements, particularly when in opposition. In this case, by making concessions to the AVWM, Labor stood to gain electorally, and was better placed to control the movement.

Overview of Australian Military Involvement in the Vietnam War, 1962 - 1975

http://www.awm.gov.au/exhibitions/impressions/impressions.asp

PrintCloseIntroduction

Australia's military involvement in the Vietnam War was the longest in duration of any war in the country's history. It lasted from August 1962 until May 1975. The Australian commitment consisted predominantly of army personnel, but significant numbers of air force and navy personnel and some civilians also took part. According to the Nominal Roll of Australian Vietnam Veterans, almost 60,000 Australians served in Vietnam.

A total of 521 Australians died in the war: Australian Army (496); RAAF (17); RAN (8). These include three Australian servicemen who were declared "missing in action". These three are in fact believed to have been "killed in action" but have no known graves.

Australia's commitment, although substantial in terms of its military capabilities, was small in comparison with the military contributions of the United States. Over 3 million Americans served in the War and the total number of American personnel in Vietnam reached a peak of over 540,000 in 1968. About 58,000 Americans died in the Vietnam War and over 2,000 were listed as Missing in Action.

The scale of Vietnamese losses on both sides of the conflict was enormous. About 224,000 South Vietnamese military personnel and over 415,000 South Vietnamese civilians were killed. Over 1 million North Vietnamese and Viet Cong were killed and more than 300,000 were declared Missing in Action. Some 4 million Vietnamese civilians (10 per cent of the total wartime population) were killed or wounded. Overall, the total number of North and South Vietnamese killed and wounded was approximately ten times the total number of American casualties.