Australia in the Vietnam War

A Case Studies in Foreign Policy Analysis

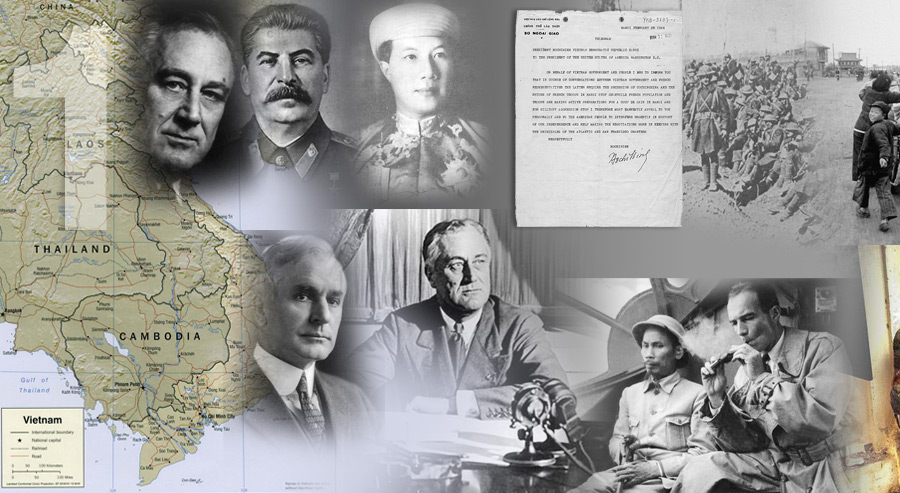

1941 - 1945 Indochina in U.S. Wartime Policy

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/pent1.html

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Volume 1

Chapter I, "Background to the Crisis, 1940-50," pp. 1-52.

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1971)Significant misunderstanding has developed concerning U.S. policy towards Indochina in the decade of World War II and its aftermath. A number of historians have held that anti-colonialism governed U.S. policy and actions up until 1950, when containment of communism supervened. For example, Bernard Fall (e.g. in his 1967 postmortem book, Last Reflections on a War) categorized American policy toward Indochina in six periods: "(1) Anti-Vichy, 1940-1945; (2) Pro-Viet Minh, 1945-1946; (3) Non-involvement, 1946-June 1950; (4) Pro-French, 1950-July 1954; (5) Non-military involvement, 1954-November 1961; (6) Direct and full involvement, 1961- ." Commenting that the first four periods are those "least known even to the specialist," Fall developed the thesis that President Roosevelt was determined "to eliminate the French from Indochina at all costs," and had pressured the Allies to establish an international trusteeship to administer Indochina until the nations there were ready to assume full independence. This obdurate anti-colonialism, in Fall's view, led to cold refusal of American aid for French resistance fighters, and to a policy of promoting Ho Chi Minh and the Viet Minh as the alternative to restoring the French bonds. But, the argument goes, Roosevelt died, and principle faded; by late 1946, anti-colonialism mutated into neutrality. According to Fall: "Whether this was due to a deliberate policy in Washington or, conversely, to an absence of policy, is not quite clear. . . . The United States, preoccupied in Europe, ceased to be a diplomatic factor in Indochina until the outbreak of the Korean War." In 1950, anti-communism asserted itself, and in a remarkable volte-face, the United States threw its economic and military resources behind France in its war against the Viet Minh. Other commentators, conversely-prominent among them, the historians of the Viet Minh-have described U.S. policy as consistently condoning and assisting the reimposition of French colonial power in Indochina, with a concomitant disregard for the nationalist aspirations of the Vietnamese.

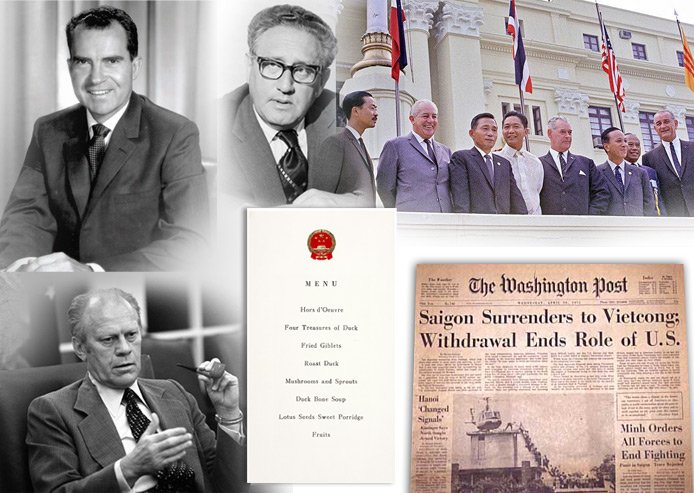

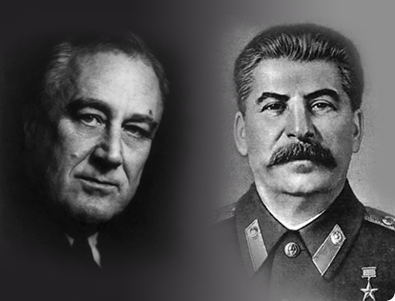

1943 Roosevelt and Stalin Discuss the Future of French Rule in Indochina

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/fdrjs.htm

PrintCloseRoosevelt and Stalin Discuss the Future of French Rule in Indochina, Teheran Conference, November 28, 1943, from Major Problems in American Foreign Policy, Volume II: Since 1914, 4th edition, edited by Thomas G. Paterson and Dennis Merrill (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1995), p. 189.

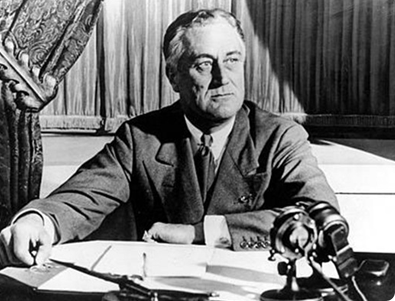

The President [FDR] said that Mr. Churchill was of the opinion that France would be very quickly reconstructed as a strong nation, but he did not personally share this view since he felt that many years of honest labor would be necessary before France would be re-established. He said the first necessity for the French, not only for the Government but the people as well, was to become honest citizens.

Marshal [Josef] Stalin agreed and went on to say that he did not propose to have the Allies shed blood to restore Indochina, for example, to the old French colonial rule. He said that the recent events in the Lebanon [where the French ended their mandate] made public service the first step toward the independence of people who had formerly been colonial subjects. He said that in the war against Japan, in his opinion, that in addition to military missions, it was necessary to fight the Japanese in the political sphere as well, particularly in view of the fact that the Japanese had granted the least nominal independence to certain colonial areas. He repeated that France should not get back Indochina and that the French must pay for their criminal collaboration with Germany.

The President said he was 100% in agreement with Marshal Stalin and remarked that after 100 years of French rule in Indochina, the inhabitants were worse off than they had been before.

The President continued on the subject of colonial possessions, but he felt it would be better not to discuss the question of India with Mr. Churchill, since the latter had no solution of that question, and merely proposed to defer the entire question to the end of the war. Marshal Stalin agreed that this was a sore spot with the British.

Franklin Roosevelt Memorandum to Cordell Hull

January 24, 1944

PrintCloseFrom Major Problems in American Foreign Policy, Volume II: Since 1914, 4th edition, edited by Thomas G. Paterson and Dennis Merrill (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1995), p. 189.

I saw Halifax [Lord Halifax, British ambassador to the United States] last week and told him quite frankly that it was perfectly true that I had, for over a year, expressed the opinion that Indo-China should not go back to France but that it should be administered by an international trusteeship. France has had the country-thirty million inhabitants for nearly one hundred years, and the people are worse off than they were at the beginning.

As a matter of interest, I am wholeheartedly supported in this view by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek [of China] and by Marshal Stalin. I see no reason to play in with the British Foreign Office in this matter. The only reason they seem to oppose it is that they fear the effect it would have on their own possessions and those of the Dutch. They have never liked the idea of trusteeship because it is, in some instances, aimed at future independence. This is true in the case of IndoChina.

Each case must, of course, stand on its own feet, but the case of Indo-China is perfectly clear. France has milked it for one hundred years. The people of IndoChina are entitled to something better than that.

1945 Abdiction of Bao Dai, Emperor of Annam

PrintCloseThe happiness of the people of Vietnam!

The Independence of Vietnam!

To achieve these ends, we have declared ourself ready for any sacrifice and we desire that our sacrifice be useful to the people.

Considering that the unity of all our compatriots is at this time our country's need, we recalled to our people on August 22: "In this decisive hour of our national history, union means life and division means death."

In view of the powerful democratic spirit growing in the north of our kingdom, we feared that conflict between north and south could be inevitable if we were to wait for a National Congress to decide us, and we know that this conflict, if it occurred, would plunge our people into suffering and would play the game of the invaders.

We cannot but have a certain feeling of melancholy upon thinking of our glorious ancestors who fought without respite for 400 years to aggrandise our country from Thuan Hoa to Hatien.

Despite this, and strong in our convictions, we have decided to abdicate and we transfer power to the democratic Republican Government.

Upon leaving our throne, we have only three wishes to express:

- We request that the new Government take care of the dynastic temples and royal tombs.

We request the new Government to deal fraternally with all the parties and groups which have fought for the independence of our country even though they have not closely followed the popular movement; to do this in order to give them the opportunity to participate in the reconstruction of the country and to demonstrate that the new regime is built upon the absolute union of the entire population. - We invite all parties and groups, all classes of society, as well as the royal family, to solidarize in unreserved support of the democratic Government with a view to consolidating the national independence.

As for us, during twenty years' reign, we have known much bitterness. Henceforth, we shall be happy to be a free citizen in an independent country. We shall allow no one to abuse our name or the name of the royal family in order to sow dissent among our compatriots.

Long live the independence of Vietnam!

Long live our Democratic Republic!

Source: La Republique [Hanoi], Issue no.1 (October 1, 1945), translated in Harold R. Isaacs (ed.), New Cycle in Asia (1947), pp. 161-162.

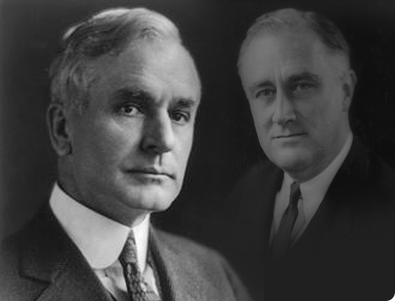

1945 Franklin Roosevelt Conversation with Charles Taussig on French Rule in Indochina

www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/fdrct.htm

PrintCloseMarch 15, 1945, from Major Problems in American Foreign Policy, Volume II: Since 1914, 4th edition, edited by Thomas G. Paterson and Dennis Merrill (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1995), p. 190.

The President [FDR] said he was concerned about the brown people in the East. He said that there are 1,100,000,000 brown people. In many Eastern countries, they are ruled by a handful of whites and they resent it. Our goal must be to help them achieve independence--1 ,100,000,000 potential enemies are dangerous. He said he included the 450,000,000 Chinese in that. He then added, Churchill doesn't understand this.

The President said he thought we might have some difficulties with France in the matter of colonies. I said that I thought that was quite probable and it was also probable the British would use France as a "stalking horse."

I asked the President if he had changed his ideas on French Indo-China as he had expressed them to us at the luncheon with [British secretary of state for the colonies Oliver] Stanley. He said no he had not changed his ideas; that French Indo-China and New Caledonia should be taken from France and put under a trusteeship. The President hesitated a moment and then said--well if we can get the proper pledge from France to assume for herself the obligations of a trustee, then I would agree to France retaining these colonies with the proviso that independence was the ultimate goal. I asked the President if he would settle for self-government. He said no. I asked him if he would settle for dominion status. He said no--it must be independence. He said that is to be the policy and you can quote me in the State Department.

Franklin Roosevelt on French Rule in Indochina, Press Conference, February 23, 1945

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/fdrpc.htm

PrintCloseFrom Major Problems in American Foreign Policy, Volume II: Since 1914, 4th edition, edited by Thomas G. Paterson and Dennis Merrill (Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath and Company, 1995), p. 190.

With the Indo-Chinese, there is a feeling they ought to be independent but are not ready for it. I suggested at the time [19431, to Chiang, that Indo-China be set up under a trusteeship--have a Frenchman, one or two Indo-Chinese, and a Chinese and a Russian because they are on the coast, and maybe a Filipino and an American--to educate them for self-government. It took fifty years for us to do it in the Philippines.

Stalin liked the idea. China liked the idea. The British don't like it. It might bust up their empire, because if the Indo-Chinese were to work together and eventually get their independence, the Burmese might do the same thing to England. The French have talked about how they expect to recapture Indo-China, but they haven't got any shipping to do it with. It would only get the British mad. Chiang would go along. Stalin would go along. As for the British, it would only make the British mad. Better to keep quiet just now.

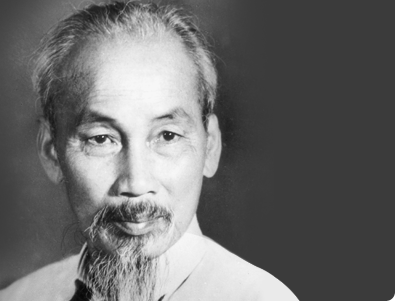

Telegram from President Hochiminh

HANOI FEBRUARY 29 1946

PrintCloseTELEGRAM

PRESIDENT HOCHIMINH VIETNAM DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC HANOI TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA WASHINGTON D.C.

ON BEHALF OF VIETNAM GOVERNMENT AND PEOPLE I BEG TO INFORM YOU THAT IN COURSE OF CONVERSATION BETWEEN VIETNAM GOVERNMENT AND FRENCH REPRESENTATIVES THE LATTER REQUIRE THE SECESSION OF COCHINCHINA AND THE RETURN OF FRENCH TROOPS IN HANOI STOP MEANWHILE FRENCH POPULATION AND TROOPS ARE MAKING ACTIVE PREPARATIONS FOR A COUP DE MAIN IN HANOI AND FOR MILITARY AGGRESSION STOP I THEREFORE MOST EARNESTLY APPEAL TO YOU PERSONALLY AND TO THE AMERICAN PEOPLE TO INTERFERE URGENTLY IN SUPPORT OF OUR INDEPENDENCE AND HELP MAKING THE NEGOTIATIONS MORE IN KEEPING WITH THE PRINCIPLES OF THE ATLANTIC AND SAN FRANCISCO CHARTERS

RESPECTFULLY

HOCHIMINH

1946 Agreement on the Independence of Vietnam

coombs.anu.edu.au/~vern/van_kien/indagree.html

PrintClose(MARCH, 1946)

- The French Government recognises the Republic of Vietnam as a free state, having its Government. its Parliament, its army, and its finances, and forming part of the Indochinese Federation and the French Union.

With regard to the unification of the three Ky (Nam Ky, or Cochin China, Trung Ky, or Annam, Bac Ky, or Tonkin), the French Government undertakes to follow the decisions of the people consulted by referendum.- The Government of Vietnam declares itself ready to receive the French army in friendly fashion when, in accord with international agreements, it relieves the Chinese troops. An annex attached to the present Preliminary Convention will fix the terms under which the operation of relief will take place.

- The stipulations formulated above shall enter into ef- fect immediately upon exchange of signatures. Each of the contracting parties shall take necessary steps to end hos- tilities, to maintain troops in their respective positions, and to create an atmosphere favourable for the immediate opening of friendly and frank negotiations. These negotiations shall deal particularly with the diplomatic relations between Vietnam and foreign states, the future status of Indochina, and economic and cultural interests. Hanoi, Saigon, and Paris may be indicated as the locales of the negotiations.

Signed: Sainteny, Ho Chi Minh, Vu Hong Khanh

Source: Bulletin Hebdomada;re Ministere de la France d'Outremer, no. 67 (March 18, 1946) translated in Harold R. Isaacs (ed.), New Cycle in Asia (1947), pp. 161-162.

Accord Between France and the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, 6 March 1946

www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/int2.htm

PrintClose

- The French Government recognizes the Vietnamese Republic as a Free State having its own Government, its own Parliament, its own Army and its own Finances, forming part of the Indochinese Federation and of the French Union. In that which concerns the reuniting of the three "Annamite Regions" [Cochinchina, Annam, Tonkin] the French Government pledges itself to ratify the decisions taken by the populations consulted by referendum.

- The Vietnamese Government declares itself ready to welcome amicably the French Army when, conforming to international agreements, it relieves the Chinese Troops. A Supplementary Accord, attached to the present Preliminary Agreement, will establish the means by which the relief operations will be carried out.

- The stipulations formulated above will immediately enter into force. Immediately after the exchange of signatures, each of the High Contracting Parties will take all measures necessary to stop hostilities in the field, to maintain the troops in their respective positions, and to create the favorable atmosphere necessary to the immediate opening of friendly and sincere negotiations. These negotiations will deal particularly with:

- diplomatic relations of Viet-nam with Foreign States

- the future law of Indochina

- French interests, economic and cultural, in Viet-nam.

Hanoi, Saigon or Paris may be chosen as the seat of the conference.

DONE AT HANOI, the 6th of March 1946

Signed: Sainteny

Signed: Ho Chi Minh and Vu Hong Khanh

1949 Communists win the Chinese Civil War

PrintCloseThe Chinese Communists win the civil war in China against the US supported Guomindang and the People's Republic of China is established by Mao Zedong on October 1 1949.

1950 United States Recognition of Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/usrecog.htm

PrintCloseStatement by the Department of State, February 7, 1950

(On March 8, 1949, France signed an agreement with the state of Vietnam under Bao Dai, agreeing to recognize the independence of Vietnam. Similar agreements were later signed with Cambodia and Laos.)

The Government of the United States has accorded diplomatic recognition to the Governments of the State of Viet Nam, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Kingdom of Cambodia.

The President, therefore, has instructed the American consul general at Saigon to inform the heads of Government of the State of Viet Nam, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Kingdom of Cambodia that we extend diplomatic recognition to their Governments and look for-ward to an exchange of diplomatic representatives between the United States and these countries.

Our diplomatic recognition of these Governments is based on the formal establishment of the State of Viet Nam, the Kingdom of Laos, and the Kingdom of Cambodia as independent states within the French Union; this recognition is consistent with our fundamental policy of giving support to the peaceful and democratic evolution of dependent peoples toward self-government and independence.

In June of last year, this Government expressed its gratification at the signing of the France-Viet Namese agreements of March 8, which provided the basis for the evolution of Viet Namese independence within the French Union. These agreements, together with similar accords between France and the Kingdoms of Laos and Cambodia, have now been ratified by the French National Assembly and signed by the President of the French Republic. This ratification has established the independence of Viet Nam, Laos, and Cambodia as associated states within the French Union.

It is anticipated that the full implementation of these basic agreements and of supplementary accords which have been negotiated and are awaiting ratification will promote political stability and the growth of effective democratic institutions in Indochina. This Government is considering what steps it may take at this time to further these objectives and to assure, in collaboration with other like-minded nations, that this development shall not be hindered by internal dissension fostered from abroad.

The status of the American consulate general in Saigon will be raised to that of a legation, and the Minister who will be accredited to all three states will be appointed by the President.

Source: U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, 90th Congress, 1st Session, Background Information Relating to Southeast Asia and Vietnam (3d Revised Edition) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, July 1967), pp. 43-44.

1950 Report by the National Security Council on the position of the United States with respect to Indochina

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/doc1.htm

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Volume 1

Document 1, Report by the National Security Council on the Position of the United States with Respect to Indochina, 27 February 1950, pp. 361-2.[Document 1]

27 February 1950

REPORT BY THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL ON THE POSITION OF THE UNITED STATES WITH RESPECT TO INDOCHINA

THE PROBLEM

1. To undertake a determination of all practicable United States measures to protect its security in Indochina and to prevent the expansion of communist aggression in that area.

1950 Extension of Military and Economic Aid

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/milext.htm

PrintCloseEXTENSION OF MILITARY AND ECONOMIC AID: Statement by the Secretary of State, May 8, 1950

(Hostilities between the French and Viet Minh Forces began late in 1946 and gradually worsened until the Geneva Agreements of 1954. This statement marks the beginning of U.S. military and economic assistance to the Associated States and France to restore stability in the area. Formal agreements were signed later.)

The [French] Foreign Minister and I have just had an exchange of views on the situation m Indochina and are in general agreement both as to the urgency of the situation in that area and as to the necessity for remedial action. We have noted the fact that the problem of meeting the threat to the security of Viet Nam, Cambodia, and Laos which now enjoy independence within the French Union is primarily the responsibility of France and the Governments and peoples of Indochina. The United States recognizes that the solution of the Indochina problem depends both upon the restoration of security and upon the development of genuine nationalism and that United States assistance can and should contribute to these major objectives.

The United States Government, convinced that neither national independence nor democratic evolution exist in any area dominated by Soviet imperialism, considers the situation to be such as to warrant its according economic aid and military equipment to the Associated States of Indochina and to France in order to assist them in restoring stability and permitting these states to pursue their peaceful and democratic development.

Source: U.S. Congress, Senate, Committee on Foreign Relations, 90th Congress, 1st Session, Background Information Relating to Southeast Asia and Vietnam (3d Revised Edition) (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, July 1967), p. 44.

1950 - 1954 U.S. Involvement in the Franco-Viet Minh War 1950 - 1954

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/pent5.htm

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Chapter 2, "U.S. Involvement in the Franco-Viet Minh War, 1950-1954"

(Boston: Beacon Press, 1971)Section 1, pp. 53-75

Foreword

This portion of the study treats U.S. policy towards the war in Indochina from the U.S. decision to recognize the Vietnamese Nationalist regime of the Emperor Bao Dai in February, 1950, through the U.S. deliberations on military intervention in late 1953 and early 1954.

Summary

It has been argued that even as the U.S. began supporting the French in Indochina, the U.S. missed opportunities to bring peace, stability and independence to Vietnam. The issues arise from the belief on the part of some critics that (a) the U.S. made no attempt to seek out and support a democratic-nationalist alternative in Vietnam; and (b) the U.S. commanded, but did not use, leverage to move the French toward granting genuine Vietnamese independence.

Security Treaty Between the United States, Australia, and New Zealand (ANZUS)

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/usmu002.asp

PrintCloseThe Parties to this Treaty,

Reaffirming their faith in the purposes and principles of the Charter of the United Nations and their desire to live in peace with all peoples and all Governments, and desiring to strengthen the fabric of peace in the Pacific Area,

Noting that the United States already has arrangements pursuant to which its armed forces are stationed in the Philippines,(2) and has armed forces and administrative responsibilities in the Ryukyus, and upon the coming into force of the Japanese Peace Treaty may also station armed forces in and about Japan to assist in the preservation of peace and security in the Japan Area,(3)

Recognizing that Australia and New Zealand as members of the British Commonwealth of Nations have military obligations outside as well as within the Pacific Area,

Desiring to declare publicly and formally their sense of unity, so that no potential aggressor could be under the illusion that any of them stand alone in the Pacific Area, and

Desiring further to coordinate their efforts for collective defense for the preservation of peace and security pending the development of a more comprehensive system of regional security in the Pacific Area,

Therefore declare and agree as follows:

ARTICLE I

The Parties undertake, as set forth in the Charter of the United Nations, to settle any international disputes in which they may be involved by peaceful means in such a manner that international peace and security and justice are not endangered and to refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force in any manner inconsistent with the purposes of the United Nations.

ARTICLE II

In order more effectively to achieve the objective of this Treaty the Parties separately and jointly by means of continuous and effective self-help and mutual aid will maintain and develop their individual and collective capacity to resist armed attack.

ARTICLE III

The Parties will consult together whenever in the opinion of any of them the territorial integrity, political independence or security of any of the Parties is threatened in the Pacific.

ARTICLE IV

Each Party recognizes that an armed attack in the Pacific Area on any of the Parties would be dangerous to its own peace and safety and declares that it would act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes.

Any such armed attack and all measures taken as a result thereof shall be immediately reported to the Security Council of the United Nations. Such measures shall be terminated when the Security Council has taken the measures necessary to restore and maintain international peace and security.

ARTICLE V

For the purpose of Article IV, an armed attack on any of the Parties is deemed to include an armed attack on the metropolitan territory of any of the Parties, or on the island territories under its jurisdiction in the Pacific or on its armed forces, public vessels or aircraft in the Pacific.

ARTICLE VI

This Treaty does not affect and shall not be interpreted as affecting in any way the rights and obligations of the Parties under the Charter of the United Nations or the responsibility of the United Nations for the maintenance of international peace and security.

ARTICLE VII

The Parties hereby establish a Council, consisting of their Foreign Ministers or their Deputies, to consider matters concerning the implementation of this Treaty. The Council should be so organized as to be able to meet at any time.

ARTICLE VIII

Pending the development of a more comprehensive system of regional security in the Pacific Area and the development by the United Nations of more effective means to maintain international peace and security, the Council, established by Article VII, is authorized to maintain a consultative relationship with States, Regional Organizations, Associations of States or other authorities in the Pacific Area in a position to further the purposes of this Treaty and to contribute to the security of that Area.

ARTICLE IX

This Treaty shall be ratified by the Parties in accordance with their respective constitutional processes. The instruments of ratification shall be deposited as soon as possible with the Government of Australia, which will notify each of the other signatories of such deposit. The Treaty shall enter into force as soon as the ratifications of the signatories have been deposited.

ARTICLE X

This Treaty shall remain in force indefinitely. Any Party may cease to be a member of the Council established by Article VII one year after notice has been given to the Government of Australia, which will inform the Governments of the other Parties of the deposit of such notice.

ARTICLE XI

This Treaty in the English language shall be deposited in the archives of the Government of Australia. Duly certified copies thereof will be transmitted by that Government to the Governments of each of the other signatories.

IN WITNESS WHEREOF the undersigned Plenipotentiaries have signed this Treaty.

DONE at the city of San Francisco this first day of September, 1951.

(1) TIAS 2493; 3 UST 3423-3425. Ratification advised by the Senate, Mar. 20, 1952, ratified by the President, Apr.15, 1952; entered into force, Apr. 29, 1952.

(2) A Decade of American Foreign Policy, pp. 881-885 and 869-881.

(3) See article 6 of the Japanese peace treaty (extra, p. 428) and the security treaty with Japan.

1952 The Defence of Indochina

http://avalon.law.yale.edu/20th_century/inch012.asp

PrintCloseIndochina - The Defense of Indochina: Communiqué Regarding Discussions Between Representatives of the United States, France, Viet-Nam, and Cambodia, June 18, 1952 (1)

Mr. Jean Letourneau, Minister in the French Cabinet for the Associated States in Indochina, has just concluded a series of conversations with U.S. Government officials from the Department of State Department of Defense, the Office of Director for Mutual Security, the Mutual Security Agency, and Department of the Treasury. The Ambassadors of Cambodia and Viet-Nam have also participated in these talks.

The principle which governed this frank and detailed exchange of views and information was the common recognition that the struggle in which the forces of the French Union and the Associated States are engaged against the forces of Communist aggression in Indochina is an integral part of the world-wide resistance by the Free Nations to Communist attempts at conquest and subversion. There was unanimous satisfaction over the vigorous and successful course of military operations, in spite of the continuous comfort and aid received by the Communist forces of the Viet-Minh from Communist China. The excellent performance of the Associated States' forces in battle was found to be a source of particular encouragement. Special tribute was paid to the 52,000 officers and men of the French Union and Associated States' armies who have been lost in this six years' struggle for freedom in Southeast Asia and to the 75,000 other casualties.

In this common struggle, however, history, strategic factors, as well as local and general resources require that the free countries concerned each assume primary responsibility for resistance in the specific areas where Communism has resorted to force of arms. Thus the United States assumes a large share of the burden in Korea while France has the primary role in Indochina. The partners, however, recognize the obligation to help each other in their areas of primary responsibility to the extent of their capabilities and within the limitations imposed by their global obligations as well as by the requirements in their own areas of special responsibility. It was agreed that success in this continuing struggle would entail an increase in the common effort and that the United States for its part will, therefore, within the limitations set by Congress, take steps to expand its aid to the French Union. It was further agreed that this increased assistance over and above present U.S. aid for Indochina, which now approximates one third of file total cost of Indochina operations, would be especially devoted to assisting France in the building of the national armies of the Associated States.

Mr. Letourneau reviewed the facts which amply demonstrate the determination of the Associated States to pursue with increased energy the strengthening of their authority and integrity both against internal subversion and against external aggression.

In this connection Mr. Letourneau reminded the participants that the accords of 1949,(2) which established the independence within the French Union of Cambodia, Laos and Viet-Nam, have been liberally interpreted and supplemented by other agreements, thus consolidating this independence. Mr. Letourneau pointed out that the governments of the Associated States now exercise full authority except that a strictly limited number of services related to the necessities of the war now in progress remain temporarily in French hands. In the course of the examination of the Far Eastern economic and trade situation, it was noted that the Governments of the Associated States are free to negotiate trade treaties and agreements of all kinds with their neighbors subject only to whatever special arrangements may be agreed between members of the French Union.

It was noted that these states have been recognized by thirty-three foreign governments.

The conversations reaffirmed the common determination of the participants to prosecute the defense of Indochina and their confidence in a free, peaceful and prosperous future for Cambodia, Laos, and Viet-Nam.

Mr.Letourneau was received by the President, Mr. Acheson, and Mr. Foster, as Acting Secretary of Defense. Mr. John Allison, Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, acted as Chairman of the U.S. Delegation participating in the conversations.

(1) Department of State Bulletin, June 30, 1952, p. 1010.

(2) Agreements of Mar. 8, 1949 (Viet-Nam), July 19, 1949 (Laos), and Nov. 8, 1949 (Cambodia) La documentation franchise, Mar. 14, 1950. The text of the agreement with Viet-Nam is also printed in Documents on International Affairs 1949-50 (London, 1953), pp. 596-608.

1953 Memorandum for the National Security Council on Further US Support

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/doc16.htm

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Volume 1

Document 16, Memorandum for the National Security Council on Further US Support for France and the Associated States of Indochina, 5 August 1953, pp. 405-410.NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL

WASHINGTONAugust 5, 1953

MEMORANDUM FOR THE NATIONAL SECURITY COUNCIL

SUBJECT: Further United States Support for France and the Associated States of Indochina

REFERENCES: A. NSC 124/2

B. NSC Action Nos. 758, 773 and 780

C. NIE-63 and NIE-91The enclosed report by the Department of State on the subject is transmitted herewith for consideration by the National Security Council of the recommendation contained in paragraph 9 thereof at its meeting on Thursday, August 6, 1953.

JAMES S. LAY, Jr.

Executive Secretarycc: The Secretary of the Treasury

The Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff

The Director of Central Intelligence

1953 President Eisenhower's Remarks on the Importance of Indochina at the Governors' Conference

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/ps7.htm

PrintClosePresident Eisenhower's Remarks at Governors' Conference, August 4, 1953, Public Papers of the Presidents, 1953, p. 540:

"I could go on enumerating every kind of problem that comes before us daily. Let us take, though, for example, one simple problem in the foreign field. You have seen the war in Indochina described variously as an outgrowth of French colonialism and its French refusal to treat indigenous populations decently. You find it again described as a war between the communists and the other elements in southeast Asia. But you have a confused idea of where it is located--Laos, or Cambodia, or Siam, or any of the other countries that are involved. You don't know, really, why we are so concerned with the far-off southeast corner of Asia.

"Why is it? Now, first of all, the last great population remaining in Asia that has not become dominated by the Kremlin, of course, is the sub-continent of India, including the Pakistan government. Here are 350 million people still free. Now let us assume that we lose Indochina. If Indochina goes, several things happen right away. The Malayan peninsula, the last little bit of the end hanging on down there, would be scarcely defensible--and tin and tungsten that we so greatly value from that area would cease coming. But all India would be outflanked. Burma would certainly, in its weakened condition, be no defense. Now, India is surrounded on that side by the Communist empire. Iran on its left is in a weakened condition. I believe I read in the paper this morning that Mossadegh's move toward getting rid of his parliament has been supported and of course he was in that move supported by the Tudeh, which is the Communist Party of Iran. All of that weakening position around there is very ominous for the United States, because finally if we lost all that, how would the free world hold the rich empire of Indonesia? So you see, somewhere along the line, this must be blocked. It must be blocked now. That is what the French are doing.

"So, when the United States votes $400 million to help that war, we are not voting for a giveaway program. We are voting for the cheapest way that we can to prevent the occurrence of something that would be of the most terrible significance for the United States of America--our security, our power and ability to get certain things we need from the riches of the Indonesian territory, and from southeast Asia."

Source: The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Vol. 1 (Boston: Beacon Press, 1971), p. 591-2

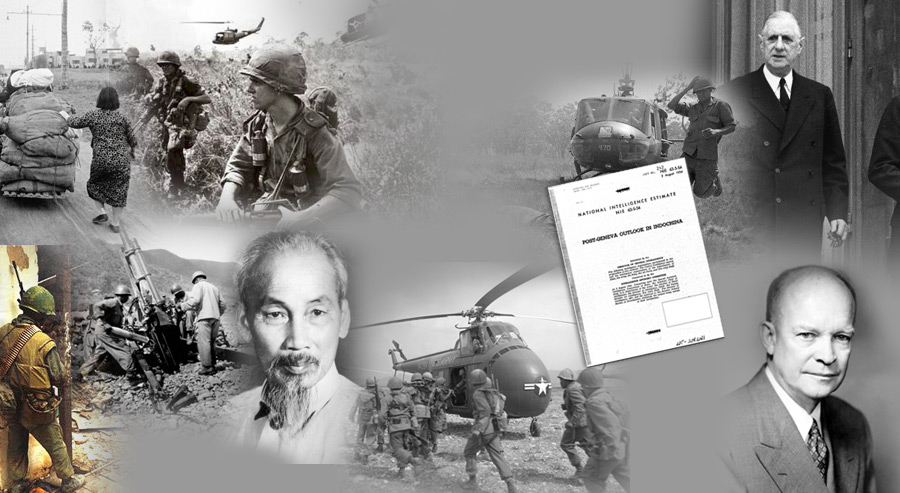

1954 National Intelligence Estimate Post-Geneva Outlook in Indochina

PrintCloseTHE PROBLEM

To assess the probable outlook in Indochina in the light of the agreements reached at the Geneva conference.

CONCLUSIONS

1. The signing of the agreements at Geneva has accorded international recognition to Communist military and political power in Indochina and has given that power a defined geographic base.

2. We believe that the Communists will not give up their objective of securing control of all Indochina but will, without violating the armistice to the extent of launching an armed invasion to the south or west, pursue their objective by political, psychological, and paramilitary means.

3. We believe the Communists will consolidate control over North Vietnam with little difficulty. Present indications are that the Viet Minh will pursue a moderate political program, which together with its strong military posture, will be calculated to make that regime appeal to the nationalist feelings of the Vietnamese population generally. It is possible, however, that the Viet Minh may find it desirable or necessary to adopt a strongly repressive domestic program which would diminish its appeal in South Vietnam. In any event, from its new territorial base, the Viet Minh will intensify Communist activities throughout Indochina.

1954 Eisenhower explains the Domino Theory

https://facultystaff.richmond.edu/~ebolt/history398/DominoTheory.html

PrintCloseQ. Robert Richards, Copley Press: Mr. President, would you mind commenting on the strategic importance of Indochina to the free world? I think there has been across the country some lack of understanding on just what it means to us.

The President: You have of course, both the specific and the general when you talk about such things.

First of all, you have the specific value of a locality in its production of materials that the world needs.

Then you have the possibility that many human beings pass under a dictatorship that is inimical to the free world.

Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the "falling domino" principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences.

Now, with respect to the first one, two of the items from this particular area that the world uses are tin and tungsten. They are very important. There are others, of course, the rubber plantations and so on.

Then with respect to more people passing under this domination, Asia, after all, has already lost some 450 million of its peoples to the Communist dictatorship, and we simply can't afford greater losses.

But when we come to the possible sequence of events, the loss of Indochina, of Burma, of Thailand, of the Peninsula, and Indonesia following, now you begin to talk about areas that not only multiply the disadvantages that you would suffer through loss of materials, sources of materials, but now you are talking about millions and millions and millions of people.

Finally, the geographical position achieved thereby does many things. It turns the so-called island defensive chain of Japan, Formosa, of the Philippines and to the southward; it moves in to threaten Australia and New Zealand.

It takes away, in its economic aspects, that region that Japan must have as a trading area or Japan, in turn, will have only one place in the world to go - that is, toward the Communist areas in order to live.

So, the possible consequences of the loss are just incalculable to the free world

Excerpt from Eisenhower's press conference of April 7, 1954

1954 Request for Technical Counter-Sabotage Guidance

MEMORANDUM FOR: Deputy Chief, WHD

PrintClose1. Several weeks ago Ambassador Willauer received a request from the Chief of the [ ] Air Force for the services of an Air Force technical specialist to assist the [ ] Air Force in combatting sabotage problems. The matter was referred to the Air Force and it was determined that under the existing treaty the United States Government was not authorized to offer the services of a person with such capabilities to the [ ] government.

2. A preliminary examination of WHD assets revealed that the Division does not have a person with the qualifications available for the assignment. In view of this, the [ ] request was not given further attention.

3. It has become apparent in recent high-level meetings with the Department of State that Projects PBSUCCESS may be cancelled, or, more probably, brought in consonance with current State Department thinking. This revision may have a rather positive impact upon our relations with [ ].

If we pull out of the paramilitary effort suddenly, and it now appears we might do just that, it would be well to have something to offer the [ ] government to indicate at least that we are [ ] [ ].

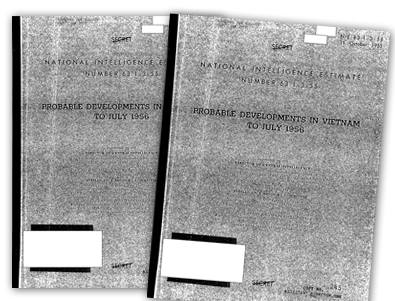

Probable development in Indochina through mid-1954 The Pentagon Papers

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/doc15.htm

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Volume 1

Document 15, National Intelligence Estimate-91, "Probable Developments in Indochina through 1954," 4 June 1953, pp. 391-404.THE PROBLEM

To estimate French Union and Communist capabilities and probable courses of action with respect to Indochina and the internal situation throughout Indochina through mid-1954.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Unless there is a marked improvement in the French Union military position in Indochina, political stability in the Associated States and popular support of the French Union effort against the Viet Minh will decline. We believe that such marked improvement in the military situation is not likely, though a moderate improvement is possible. The over-all French Union position in Indochina therefore will probably deteriorate during the period of this estimate.

2. The lack of French Union military successes, continuing Indochinese distrust of ultimate French political intentions, and popular apathy will probably continue to prevent a significant increase in Indochinese will and ability to resist the Viet Minh.

3. We cannot estimate the impact of the new French military leadership. However, we believe that the Viet Minh will retain the military initiative and will continue to attack territory in the Tonkin delta and to make incursions into areas outside the delta. The Viet Minh will attempt to consolidate Communist con-trot in "Free Laos" and will build up supplies in northern Laos to support further penetrations and consolidation in that country. The Viet Minh will almost certainly intensify political warfare, including guerrilla activities, in Cambodia.

4. Viet Minh prestige has been increased by the military successes of the past year, and the organizational and administrative effectiveness of the regime will probably continue to grow.

5. The French Government will remain under strong and increasing domestic pressure to reduce the French military commitment in Indochina, and the possibility cannot be excluded that this pressure will be successful. However, we believe that the French will continue without enthusiasm to maintain their present levels of troop strength through mid-1954 and will support the planned development of the national armies of the Associated States.

6. We believe that the Chinese Communists will continue and possibly increase their present support of the Viet Minh. However, we believe that whether or not hostilities are concluded in Korea, the Chinese Communists will not invade Indochina during this period. The Chinese Communists will almost certainly retain the capability to intervene so forcefully in Indochina as to overrun most of the Tonkin delta area before effective assistance could be brought to bear.

7. We believe that the Communist objective to secure control of all Indochina will not be altered by an armistice in Korea or by Communist "peace" tactics. However, the Communists may decide that "peace" maneuvers in Indochina would contribute to the attainment of Communist global objectives, and to the objective of the Viet Minh.

8. If present trends in the Indochinese situation continue through mid-1954, the French Union political and military position may subsequently deteriorate very rapidly.

1954 Memorandum for the Special Committee

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon/doc24.htm

PrintCloseThe Pentagon Papers

Gravel Edition

Volume 1

Document 24, Memorandum for the President's Special Committee, "Military Implications of the US Position on Indochina in Geneva," 17 March 1954, pp. 451-54.March 17, 1954

MEMORANDUM FOR THE SPECIAL COMMITTEE, NSC

Subject: Military Implications of the U.S. Position on Indochina in Geneva

1. The attached analysis and recommendations concerning the U.S. position in Geneva have been developed by a Subcommittee consisting of representatives of the Department of Defense, JCS, State, and CIA.

2. This paper reflects the conclusions of the Department of Defense and the JCS and has been collaborated with the State Department representatives who have reserved their position thereon.

3. In brief, this paper concludes that from the point of view of the U.S. strategic position in Asia, and indeed throughout the world, no solution to the Indochina problem short of victory is acceptable. It recommends that this be the basis for the U.S. negotiating position prior to and at the Geneva Conference.

4. It also notes that, aside from the improvement of the present military situation in Indochina, none of the courses of action considered provide a satisfactory solution to the Indochina war.

5. The paper notes that the implications of this position are such as to merit consideration by the NSC and the President.

6. I recommend that the Special Committee note and approve this report and forward it with the official Department of State views to the NSC.

G. B. Erskine

General, USMC (Ret)

Chairman, Sub-committee

President's Special Committee

1954 Geneva Accords

http://vietnam-war.commemoration.gov.au/vietnam-war/background.php

PrintCloseThe distant origins of the Vietnam War lie in the nineteenth-century colonisation of Indochina (Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam) by France. French rule lasted until 1940 when the Japanese, embarking on a series of conquests in Southeast Asia and eventually war against Western powers, occupied Vietnam. Japan's defeat in 1945 saw France seeking to regain control of her erstwhile colonies. Establishing the state of Vietnam, France installed the former emperor, Bao Dai, as head of state. For many Vietnamese, however, the end of the Japanese occupation meant the chance for independence, duly proclaimed by Ho Chi Minh, leader of Vietnam's Communist Party, in September 1945.

France refused to accept the declaration, and eight years of war followed, ending with the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. The peace settlement, known as the Geneva Accords, divided the country; the North under the communist Ho Chi Minh, and the South under President Ngo Dinh Diem who had deposed Bao Dai and proclaimed the Republic of Vietnam in October 1955.

The Geneva Accords mandated that a Vietnam-wide election, aimed at reunifying the divided country, be held in 1956. Diem claimed that the people of the North could not vote freely, and with the backing of the United States, he refused to participate. Relations between the two Vietnams grew increasingly tense and in 1960 the North, aiming to overthrow Diem and reunite the country under communist rule, proclaimed the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam.

In 1956 four officers from the South Vietnamese army toured military establishments in Australia. Within six years Australians were training, and later fighting, alongside men such as these in Vietnam. In a more peaceful time these officers were photographed at the Australian War Memorial beside a statue depicting a moment from the birthplace of so many of Australia's military legends, Gallipoli. [NLA 8887621 Image courtesy of the National Library of Australia]

Known as the Viet Cong (Vietnamese Communists) and hoping to foment a general uprising, the Front embarked on a guerilla campaign throughout the South. The South Vietnamese Army proved unable to counter the insurgents' tactics and the United States, alarmed at the prospect of communism spreading throughout South-East Asia, began to significantly increase what had been a limited amount of assistance to the South. By 1962 more than 11,000 United States military advisers had arrived in the country. They represented the beginning of a build-up in United States troop numbers that would peak at more than 500,000.

1954 Memorandum for the Director of Central Intelligence

SUBJECT: Probable Communist Strategy and Tactics at Geneva

PrintClose1. In our view, the Communists see in the forthcoming negotiations at Geneva abundant opportunities to improve their position both in Asia and in Europe. They are almost certainly confident that their negotiating position regarding Indochina will be both stronger and more unified that that of the West. They also are aware that the British and French attitude toward Communist China is more flexible than that of the US and probably consider that this divergence of attitude can be exploited, particularly if discussions of China's status as a world power can be tied to the possibilities of a settlement in Indochina. They probably also believe that the establishment of a Korean armistice has created a receptivity among Western nations for a general Far Eastern settlement and that this receptivity broadens their area for manouver.

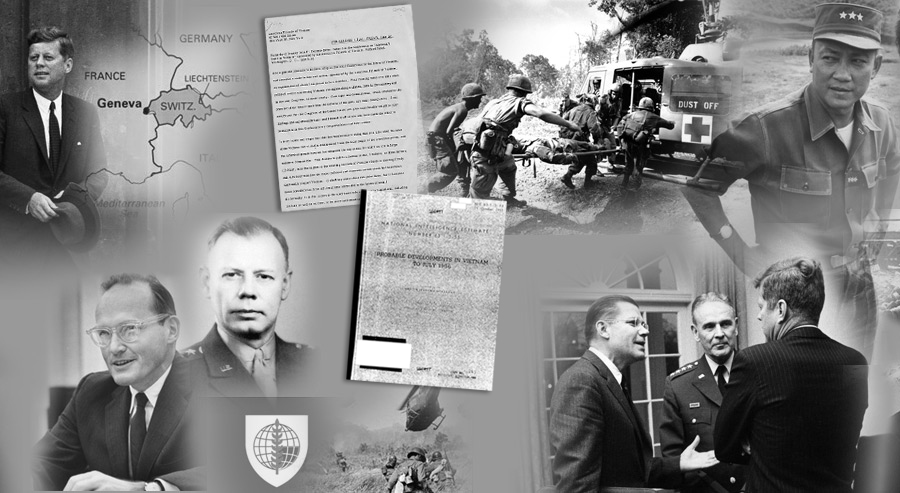

1956 Remarks of Senator John F. Kennedy at American Friends of Vietnam

FOR RELEASE 1P.M., FRIDAY, June 1st.

PrintCloseRemarks of Senator John F. Kennedy (Dem.- Mass.) at the Conference in the future of Vietnam, and America's stake in that new nation, sponsored by the American Friends of Vietnam, an organization of which I am proud to be a member. Your meeting today at a time when political events concerning Vietnam are approaching a climax, both in that country and in our own Congress, is most timely. Your topic and deliberations, which emphasize the promise of the future more that the failures of the past, are most constructive. I can assure you that the Congress of the United State will give considerable weight to your findings and recommendations; and I extend to all of you who have made the effort to participate in the Conference my congratulations and best wishes.

Probable developments in Vietnam to July 1956

PrintCloseTHE PROBLEM

To estimate the prospects for the development of a Vietnamese government with the capability to defend itself against internal subversion and uprisings and with sufficient authority and administrative ability to deal adequately with the many problems facing it, including those posed by the Geneva Agreements.

CONCLUSIONS

1. Since he became Premier in July 1954, Ngo Dinh Diem has made considerable progress toward establishing the first fully independent Vietnamese government. Nevertheless, the capability of the South Vietnamese to develop an effective government which can survive during the next few years is still in doubt. (Paras. 9, 12)

2. Assuming Diem survives and provided he continues to receive wholehearted US support, we believe he will probably be able to cope with non-Communist dissident elements and to remain in office during the period of this estimate. Moreover, providing the Communists do not exercise their capabilities to attack across the 17th Parallel or to initiate large-scale guerilla warfare in South Vietnam, Diem will probably make further progress in developing a more effective government. (Para.54)

1961 Increase in Bloc Aid to North Vietnam - Current Support Brief

PrintCloseThe dispute between the USSR and Communist China has benefited North Vietnam by encouraging a greater display of concern for its economic well being on the part of the disputants. A concrete manifestation of this has been the extension during the past year by the USSR and Communist China of large new credits amounting to $350 million for support of the first Five-Year Plan of North Vietnam (1961-65).

Although there are no indications that either China or the USSR is attempting to become a monopolist in providing aid to North Vietnam, it is apparent that neither is willing to leave the field to the sole influence of the other. It is of common interest to both the USSR and China that North Vietnam develop a well rounded economy, and the two large Communist powers have committed themselves to assist in a comprehensive and diversified economic plan. But, in view of its own economic deficiencies, the fact that China is providing any economic assistance at all to North Vietnam indicates concern that it not be deprived of an influence in this bordering state; and the largeness of its program suggests the degree of its concern. Thus, the new Soviet commitments during 1960, even though they may have resulted from motives to which the Chinese could not object, have prompted China to extend additional credits in order to retain a prominent economic role in the economy of North Vietnam.

1961 Probable Communist Reactions to Certain US Actions in South Vietnam

SPECIAL NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE

PrintCloseSUBJECT; SNIE 10-4-61: PROBABLE COMMUNIST REACTIONS TO CERTAIN US ACTIONS IN SOUTH VIETNAM

SCOPE

The purpose of this estimate is to assess Communist (Soviet, Chinese, and North Vietnamese) reactions and, where significant, non-Communist reactions to certain US military actions intended to assist the Government of Vietnam cope with the Communist threat.1)

1) Other National Intelligence Estimates pertinent to this problem are SNIE 10-2-61, "Likelihood of Major Communist Military Intervention in Mainlaid Southeast Asia," dated 27 June 1961; SNIE 58-2-61, "Probable Reactions to Certain Course of Action Concerning Laos," dated 5 July 1961; NIE 14.3/53-61, "Prospects for North and South Vietnam," dated 15 August 1961; and SNIE 53-2-61, "Bloc Support of the Communist Effort Against the Government of Vietnam," dated 5 Ocotber 1961; SNIE 10-3-61, "Probable Communist Reactions to Certain SEATO Undertakings in South Vietnam," dated 10 October 1961.

National Security Action Memorandum No. 273

THE WHITE HOUSE WASHINGTON - November 26, 1963

PrintCloseTO: The Secretary of State

The Secretary of Defence

The Director fo Central Intelligence

The Administrator, AID

The Director, USIAThe President has reviewed the discussions of South Vietnam which occurred in Honolulu, and has discussed the matter further with Ambassador Lodge. He directs that the following guidance be issued to all concerned.

1. It remains the central object of the United States in South Vietnam to assist the people and Government of that country to win their contest against the externally directed and supported Communist conspiracy. The test of all U.S. decisions and actions in this area shoule be the effectiveness of their contribution to this purpose.

2. The objectiveness of the United States with respect to the withdrawal of U.S. military personnel remain as stated in the White House statement of October 2, 1963.

3. It is a major interest of the United States Government that the present provisional government of South Vietnam should be assisted in consolidating itself and in holding and developing increased public support. All U.S. officers should conduct themselves with this objective in view

1963 DCI Briefing South Vietnam

9 July 1963

PrintCloseI. South Vietnam continues to restive over the unresolved Buddhist issue and a coup attempt is increasingly likely.

II. South Vietnam's army commander, MAjor General Tran Van Don, told a CIA officer on 8 July that there are plans by the military to overthrow President Diem

A. Don did not specify the timing of such action, but hinted that it might be within ten days. He said all but one or two general officers were agreed on the plan.

B. The military is the key to any successful move to oust the government, and Don is a respected officer. That makes this report the most substantial of a recent series of reported coup plots.

C. Among such reports are a plot centered around Diem's former security chief, Tran Kim Tuyen, alleged to have set a target date of 10 July and to be cooperating with some military elements.

III.Some of these reports may represent government efforts to smoke out disaffected elements, but Diem's handling of the Buddhist issue has caused serious stresses within the adminstration in both civilian and military circles.

A. General Don claims that the military feels it must act to prevent the Viet Cong from capitalizing on the continuing Buddhist crisis.

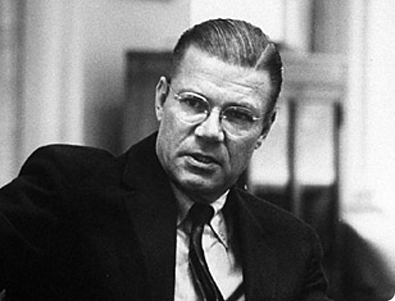

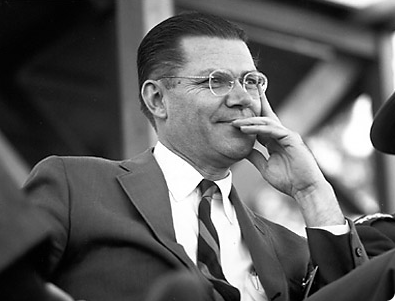

1963 Memorandum for the President Report of McNamara-Taylor Mission to South Vietnam

THE SECRETARY OF DEFENCE WASHINGTON - 2 October 1963

PrintCloseMEMORANDUM FOR THE PRESIDENT

Subject: Report of McNamara-Taylor Mission to South Vietnam

Your memorandum of 21 September 1963 directed at General Taylor and Secretary McNamara proceed to South Vietnam to appraise the military and para-military effort to defeat the Viet Cong and to consider, in consultation with Ambassador Lodge, related political and social questions. You further directed that, if the prognosis in our judgement was not hopeful, we should present our views of what action must be taken by the South Vietnam Government and what steps our Government should take to lead the Vietnamese to that action.

Accompanied by representatives of the State Department, CIA, and your Staff, we have conducted an intensive program of visits to key operational areas, supplemented by discussions with U.S. officials in all major U.S. Agencies as well as officials of the GVN and third countries.

We have also discussed our findings in detail with Ambassador Lodge, and with General Harkins and Admiral Felt

1963 Meeting in the Situation Room (Without the President)

October 3, 1963, 6:00 PM - - Subject Vietnam

PrintClosePresent: Secretary McNamara, Secretary Dillon, Under Secretary Ball, Director McCone, Adminstrator Bell, Acting Director Wilson, Under Secretary Harriman, General Krulak, Deputy Secretary Gilpatric, Assistant Secretary Hilsman, Deputy Assistant Secretary William Bundy, Mr, Janow (AID), Mr. McGeorge Bundy, General Clifton, Mr. Forrestal, Mr. Bromley Smith.

The group working on Vietnam met wihout the President to work on the recommendations growing out of the McNamara/Taylor trip to Vietnam.

Secretary McNamara said we cannot stay in the middle much longer. The program outlined in his report will push us toward a reconciliation with Diem or toward a coup to overthrow Diem. The program will have no major effect on the war effort for a period of from two to four months. Ambassador Lodge, on the basis of conversations in Saigon, would undoubtedly welcome this program as well as instructions to implement it. The question still remains, however, as to what Lodge's bargaining position is. What should Lodge ask Diem to do? We should draw up a list for Lodge and have him find out how many of our recommendations Diem would accept. This list would included the military recommendations contained in the report. As to political actions, there are several things we want Diem to do which we think would halt the erosion of public support of the government, and, hence, the resulting effect on the war effort in Vietnam. One of the important actions would be to reopen Saigon University after conversations with the school authorities. The purpose would be to re-assure the students that they need not fear arrest. In return, they would not carry out further riots in Saigon.

1963 Telegram for CINCPAC / POLAD exclusive for Admiral Felt

ACTION: AmEmbassy SAIGON - OPERATIONAL IMMEDIATE

PrintCloseEYES ONLY - AMBASSADOR LODGE

FOR CINCPAC/POLAND EXCLUSIVE FOR ADMIRAL FELT

NO FURTHER DISTRIBUTIONRe CAS Saigon 0265 reporting General Don's views; Saigon 320, Saigon 316, and Siagon 329.

It is now clear that whether military proposed martial law or whether Nhu tricked them into it, Nhu took advantage of its imposition to smash pagodas with police and Tung's Special Forces loyal to him, thus placing onus on military in eyes of world and Vietnamese people. Also clear that Nhu has maneuvered himself into commanding position.

US Government cannot tolerate situation in which power lies in Nhu and his coterie and replace them with best military and political personalities available.

If, in spite of all of your efforts, Diem remains obdurate and refuses, then we must face the possibility that Diem himself cannot be preserved.

1963 Memorandum for Mr McGeorge Bundy from CIA

SUBJECT: Events in South Vietnam Since 5 October

PrintClose19 October 1963

1. Mr McCone believes that you may find useful the attached review of recent events and developments in South Vietnam, which he has ordered distributed to the USIB agencies and members of the National Security Council.

2. Except in the military sphere, where the GVN has taken certain actions in line with the recommendations of CONMUSMACV and General Taylor, we find little to indicate that Diem and Nhu have been appreciably moved by US actions to date. Instead, they appear to be digging in for a protracted contest of wills with the US during which they will resist pressures for reform and seek to deny opportunities for additional US initiatives.

RAY S. CLINE

Deputy Director (Intelligence)

1963 Draft letter to President Diem

PrintCloseDear Mr President

1. I am sending you this letter because of the gravity of the situation which now confronts our two countries, in their relations to each other. For us in the United States, difficult and painful decisions cannot long be put off, and I know that you on your side have problems of similar gravity. Moreover, it is clear to me as I work on this problem that many of its difficulties arise from uncertainty and error in assessing the real facts of the situation. Both of our Governments, for different reasons, face great difficulties on this score. And so I think it maybe important and helpful for you to know accurately just how the situation now appears to me. In return, I shall greatly value the most candid expresion of your own assessment, and it may well be that you and I between us can work out a new understanding in place of the present troubled, confused and dangerous relation between our Governments.

2. At the outst, let me state plainly that the central purpose of my Government in all of its relations to your country is that the Communists should be defeated in their brazen effort to capture your country by force and fraud of all varieties. What we do and do not do, whether it seems right or wrong to our friends is always animated by this central purpose. You may remember that my great predecessor Abraham Lincoln once explained to a newspaperman the depth of his commitment to the preservation of the American union by saying that even on the great issue of slavery what he did or did nto do was governed by his judgement of its value in ending the diversion of our country. The United States Government gives that kind of priority to the defeat of the Communists, in all that it does in its relations with your country.

1964 Memorandum for The Director

SUBJECT: Would the Loss of South Vietnam and Laos Precipitate a "Domino Effect" in the Far East?

PrintClose9 June 1964

1. The "domino effect" appears to mean that when one nation falls to communism the impact is such as to weaken the resistence of other countries and facilitate, if not cause, their fall to communism. Most literally taken, it would imply the successive and speedy collapse of neighboring countries, as a row of dominoes falls when the first is toppled--we presume that this degree of literalness is not essential to the concept. Most specificall it means that the loss of South Vietnam and Laos would lead almost inevitably to the communization of other states in the area, and perhaps beyond the area.

2. We do not believe that the loss of Sout Vietnam and Laos would be followed by the rapic, successive communization of the other states of the Far East. Instead of a shock wave passing from one nation to the next, there would be a simultaneous, direct effect on all Far Eastern countries. With the possible exception of Cambodia, it is likely that no nation in the area would quickly succumb to communism as a result of the fall of Laos and South Vietnam. Furthermore, a continuation of the spread of communism in the area would not be inexorable, and any spread which did occur would take time--time in which the total situation might change in any of a number of ways favourable to the Communist cause.

The loss of SOuth Vietnam and Laos to the Communists* would be profoundly damaging to the US position in the Far East, most especially because the US has committed itself persistently, emphatically, and publicly to preventing Communist takeover of the two countries. Failure here would be damaging to US prestige, and would seriously debase the credibility of US will and capability to contain the spread of communism elsewhere in the areas. Our enemies would be encouraged and there would be an increased tendency among other states to move toward a greater degree of accommodation with the Communists. However, the extent to which individual countries would move away from the US towards the Communists would be significantly affected by the substance and manner of US policy in the period following the loss of Laos and South Vietnam.

1964 National Security Action Memorandum No. 298

SUBJECT: Study of Possible Redeployment of U.S. Division now Stationed in Korea

PrintCloseTO: The Secretary of State

The Secretary of Defense

The Administrator Agency for International Development

This is to request that the Secretary of State co-ordinate a joint State-AID-Defense study which will enable me to weigh and resolve the choices facing us with respect to the possible redeployment--to Hawaii--of one of the U.S. Divisions now stationed in Korea. The study should explore what sequence of U.S. actions, involving economic assistance, military assistance, diplomatic communications, and public statements, would minimize the negative effects and maximize the benefit of such a redeployment, taking into account.

--Korea's military security

--Korea's short-term political stability

--the long-term U.S. objective of stimulating Korea's social and political institutions.

"United States Policy in Vietnam", by Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense

http://www.mtholyoke.edu/acad/intrel/pentagon3/ps3.htm

PrintClose26 March 1964, Department of State Bulletin, 13 April 1964

Source: The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 3, pp. 712-715

"United States Policy in Vietnam," by Robert S. McNamara, Secretary of Defense, 26 March 1964, Department of State Bulletin, 13 April 1964, p. 562:

"At the Third National Congress of the Lao Dong (Communist) Party in Hanoi, September 1960, North Vietnam's belligerency was made explicit. Ho Chi Minh stated, 'The North is becoming more and more consolidated and transformed into a firm base for the struggle for national reunification.' At the same congress it was announced that the party's new task was 'to liberate the South from the atrocious rule of the U.S. imperialists and their henchmen.' In brief, Hanoi was about to embark upon a program of wholesale violations of the Geneva agreements in order to wrest control of South Vietnam from its legitimate government.

"To the communists, 'liberation' meant sabotage, terror, and assassination: attacks on innocent hamlets and villages and the coldblooded murder of thousands of schoolteachers, health workers, and local officials who had the misfortune to oppose the communist version of 'liberation.' In 1960 and 1961 almost 3,000 South Vietnamese civilians in and out of government were assassinated and another 2,500 were kidnaped. The communists even assassinated the colonel who served as liaison officer to the International Control Commission.

"This aggression against South Vietnam was a major communist effort, meticulously planned and controlled, and relentlessly pursued by the government in Hanoi. In 1961 the Republic of Vietnam, unable to contain the menace by itself, appealed to the United States to honor its unilateral declaration of 1954. President Kennedy responded promptly and affirmatively by sending to that country additional American advisers, arms, and aid.

1965 Memorandum for the Director

SUBJECT: Consequences of a Pause in Bombings of the DRV

PrintClose1. One of the principal dangers of interrupting the program of bombing the DRV lies in the interpretation the other side might put on such a move. The present self-imposed limits on these bombings must suggest to the Communists that US policy is already operating under considerable restraints. If these bombings were simply suspended, they might believe that their own estimates and convictions were being borne out, that US determination and will power were weakening under the pressure of Communist threats and of international and US domestic opinion. They might think that, by taking some superficial and minimal political moves, they could effectively tie up the US in debates and arguments about negotiating, thereby raising the political cost of a resumption of air strikes. And in fact it would not be easy for the US to resume its strikes.

Whatever the Communists might conclude about further intentions, they would have the opportunity to reopen some infiltration routes, increase the flow of supplies to the VC, repair bomb damage, and regroup for further operation. They would certainly use the opportunity to improve their air defenses so that a resumption of air strikes would be more costly.

1965 Implications of a certain US course of action

SPECIAL NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE

PrintCloseSUBJECT: SNIE 10-7-65: IMPLICATIONS OF A CERTAIN US COURSE OF ACTION

THE PROBLEM

To estimate Communist reaction if the US does not attack the surface-to-air missile sites, light bombers, and fighters recently furnished to the DRV by the USSR.*

DISCUSSION

1. Since April, the Soviet Union has been furnishing to North Vietnam a variety of weapons. Among these the most important are about 30 MIG-15/17s, some with limited all-weather capabilities, three SAM sites under construction near Hanoi, and eight light jet bombers (IL-28) which have been ferried across China to Phuc Yen airfield since 21 May.

We think this prohram of military assistance was initiated to deter the US from extending its air attacks to the Hanoi-Haiphong complex. In the Communist view, the deterrence would rest not so much on the combat capabilites of the weapons as on the manifestation of a deepening Soviet commitment. In effect, Hanoi and Moscow are hoping that this new program, added to other pressures on US policy (e.g., domestic and world opinion), will dissuade the US from extending air attacks northward. The Soviet program of military assistance also represents a part of Moscow's effort to increase its influence, relative to that of Communist China, on the Hanoi regime.

1964 Chances for a Stable Government in South Vietnam

SPECIAL NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE 53-64

PrintCloseSUBJECT: SNIE 53-64: CHANCES FOR A STABLE GOVERNMENT IN SOUTH VIETNAM

THE PROBLEM

To assess the chances for the emergence of a stable non-Communist regime in South Vietnam.

CONCLUSION

At present the odds are against the emergence of a stable government capable of effectively prosecuting the war in South Vietnam. Yet the situation is not hopeless: if a viable regime evolves from the present confusion it may even gain strength from the release of long-pent pressures and the sobering effect of the current crisis. Of the men on the scene, General Khanh probably has the best chance of mustering sufficient support to restore a reasonable stable and workable government.

1965 Communist and Free World Reactions to a Possible US Course of Action

SPECIAL NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE

PrintCloseSUBJECT; SNIE 10-9-65: COMMUNIST AND FREE WORLD REACTIONS TO A POSSIBLE US COURSE OF ACTION

23 July 1965

THE PROBLEM

To estimate foreign reactions, particularly those of the Communist powers, to a specified US course of action with respect to Vietnam.

ASSUMPTIONS

For purposes of this estimate, we assume that the US decides to increase its forces in South Vietnam to about 175,000 by 1 November. We further assume related decisions to call up about 225,000 reserves, to extend tours of duty at the rate of 20,000 a month, to increase the regular strength of the armed services by 400,000 over the next year, and to double draft calls.

We further assume (a) that the increase in forces would be accompanied by statements reiterating our objectives and our readiness for unconditonal discussion, (b) that US forces would be deployed so that no major grouping threatened or appeared to threaten the 17th Parallel, and (c) that we might either continue present policy with regard to air strikes or extend these strikes in North Vietnam to include attacks on land (but not sea) lines of communication from South China* and military targets in the Hanoi-Haiphong area.

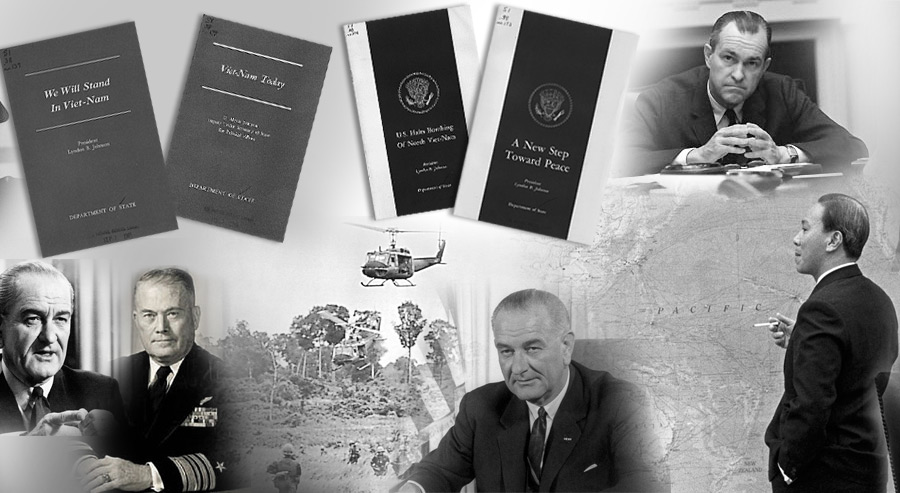

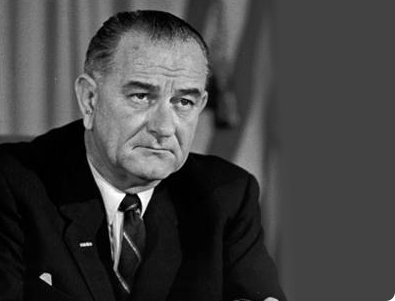

1965 We Will Stand in Viet-Nam

President Lyndon B. Johnson

PrintCloseIn this pursuit we welcome and we ask for the concern and the assistance of any nation and all nations. If the United Nations and its official or any of its 114 members can by deed or word, private initiative or public action, bring us nearer an honorable peace, then they will have the support and the gratitude of the United States of America.

I have directed Ambassador Goldberg to go to New York today and to present immediately to Secretary-General U Thant a letter from me requesting that all of the resources, energy, and immense prestige of the United Nations be employed to find ways to halt aggression and to bring peace in Viet-Nam.

1965 Communist Reactions to Possible US Actions

SPECIAL NATIONAL INTELLIGENCE ESTIMATE

PrintCloseSUBJECT: SNIE 10-3-65: COMMUNIST REACTIONS TO POSSIBLE US ACTION

THE PROBLEM

To estimate Communist reactions, particularly Soviet reactions, to a US course of sustained air attacks on North Vietnam

SCOPE NOTE

This US course is presumed to start with a public declaration outlining the new policy and linking it to the entire range of Viet Cong guerilla and terrorist activity in South Vietnam. This declaration, we further presume, makes it clear that the US means to go beyond specific reprisals for individual major Viet Cong actions and to continue air attacks until the threat to South Vietnam has been reduced to levels which the US regards as tolerable. We consider in this estimate present Communist attitudes and Communist reactions, particularly Soviet reactions, in the period before and during continuing air attacks, and during any period when these attacks are suspended.

1966 Viet-Nam Today

U. Alexis Johnson Deputy Under Sectretary of State for Political Affairs

PrintCloseI genuinely appreciate this opportunity to discuss Viet-Name with you this evening. The questions we face there are of such moment that they properly concern and trouble every thinking American.

As you of the press have so ably and repeatedly informed the American public, the problems we face are complex and the answers are not simple. Also, I know that you are fully conscious of the heavy burden you bear in providing a forum for that free and public discussion necessary for an enlightened people.

I do not this evening propose to give you any pat answers, nor do I propose to try to oversimplify the problem. What I hope to do is to share with you some of my own observations and thoughts, going back to my first personal association with Viet-Nam as a member of our delegation to the Geneva conference of 1954, my conversations with the Chinese Communists in Geneva from 1954 to 1958, my service on the SEATO Council, and most recently my service in Viet-Nam. I also want to summarize briefly the broad approach your Government is taking to this problem both in Viet-Name and in the sphere of international politics.

1967 Implications of an Unfavourable Outcome in Vietnam

PrintClosePROBLEM AND ASSUMPTIONS

1. At some stage in most debates about the Vietnam war, questions like the following emerge; what would it actually mean for the US if it failed to achieve its stated objectives in Vietnam? Are our vital interests in fact involved? Would abondonment of the effort really generate other serious dangers? Naturally, those who oppose the war tend to minimize the costs of failures, while those who support the war point ominously to far-reaching negative effects which they allege would follow such a setback. This aspect of the Vietnam argument has lacked clear and detailed definition on both sides, even though it is crucial to the Why and Wherefore of our whole involvement there.